The month of June marks the passing of two historically consequential rulers: the fourth-century Roman emperor Julian, posthumously referred to as Julian the Apostate, and the twelfth-century Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, also known as Frederick Barbarossa. Their untimely deaths shocked the Late Antique and Medieval worlds, respectively. On June 26, 363, Julian was mortally wounded in the battle of Samarra during a Roman military campaign against the Persians. According to various sources, a spear delivered by a member of the Sassanian cavalry pierced his liver, and he subsequently died from the mortal blow some three days later. June 10, 1190, marks the day on which Frederick Barbarossa drowned in the Saleph River (the Göksu in modern Turkey) in the middle of the Third Crusade, the Latin West’s attempt to recapture the Holy Land from Saladin. The deaths of both leaders in the middle of critical military campaigns generated either anxiety or derision among their contemporaries, as underscored in subsequent medieval representations of the two emperors.

Posthumous medieval representations of Julian, the last Roman emperor who championed paganism, are almost always critical. For example, a lavishly illuminated ninth-century Byzantine manuscript of Gregory Nazianzen’s homilies (Paris, BnF, gr.510, fol. 374v), depicts the ruler accompanying the pagan philosopher Maximus of Ephesus and venerating idols. In Simone Martini’s fourteenth-century fresco cycle in the Chapel of Saint Martino within the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi, the figure of Julian the Apostate serves as an arrogant, pagan, visual foil to the saintly Martin of Tours, who is shown renouncing military life for his Christian beliefs. Depictions of Julian’s death are even more damning. By the early sixth century, accounts surrounding Julian’s death shifted away from a battle against the Persians and amplified the legend of Saint Mercurius (identified as Mercurius of Caesarea in the Index database), a Byzantine soldier saint who rises from the dead and kills the pagan emperor with his lance or sword.

Although this legend developed in Eastern sources, it grew in popularity in the Medieval Latin West, even making an appearance in Jacopo de Voragine’s thirteenth-century Golden Legend. In a fourteenth-century Christherre-Chronik miniature in the Morgan Library (New York, PML, M.769, fol. 327v), the figure of Julian is portrayed as an elderly medieval monarch lanced by a fully armored Saint Mercurius astride a galloping horse.

In contrast to the overwhelmingly uncomplimentary medieval portraits of Julian the Apostate, representations of Frederick Barbarossa generally evoke the idea of imperial majesty and power. The so-called Cappenberg head (c. 1160), a reliquary that originated as a portrait of Frederick, effectively conveys an image of grandeur and stability through its precious materials and antique visual language. Yet a miniature drawn, less than a decade after his death, in Peter of Eboli’s De Rebus Sicilis (Bern, Stadtbibliothek, 120 II, fol. 107r) betrays the unease surrounding the emperor’s accidental passing. Inscribed FREDERICUS IMPERATOR IN FLUMINE DEFUNCTUS, the drawing depicts the ruler falling off his horse and drowning in the water, his crown lying ignobly in the riverbed. As if to combat the contemporary whispers that Frederick died without confessing his sins, the illuminator purposely included an image of the ruler’s soul as a swaddled infant held aloft by an angel and given to the Hand of God emerging from heaven. In so doing, the artist was participating in a larger, concerted effort to salvage Frederick Barbarossa’s reputation for posterity as a noble and most Christian emperor.

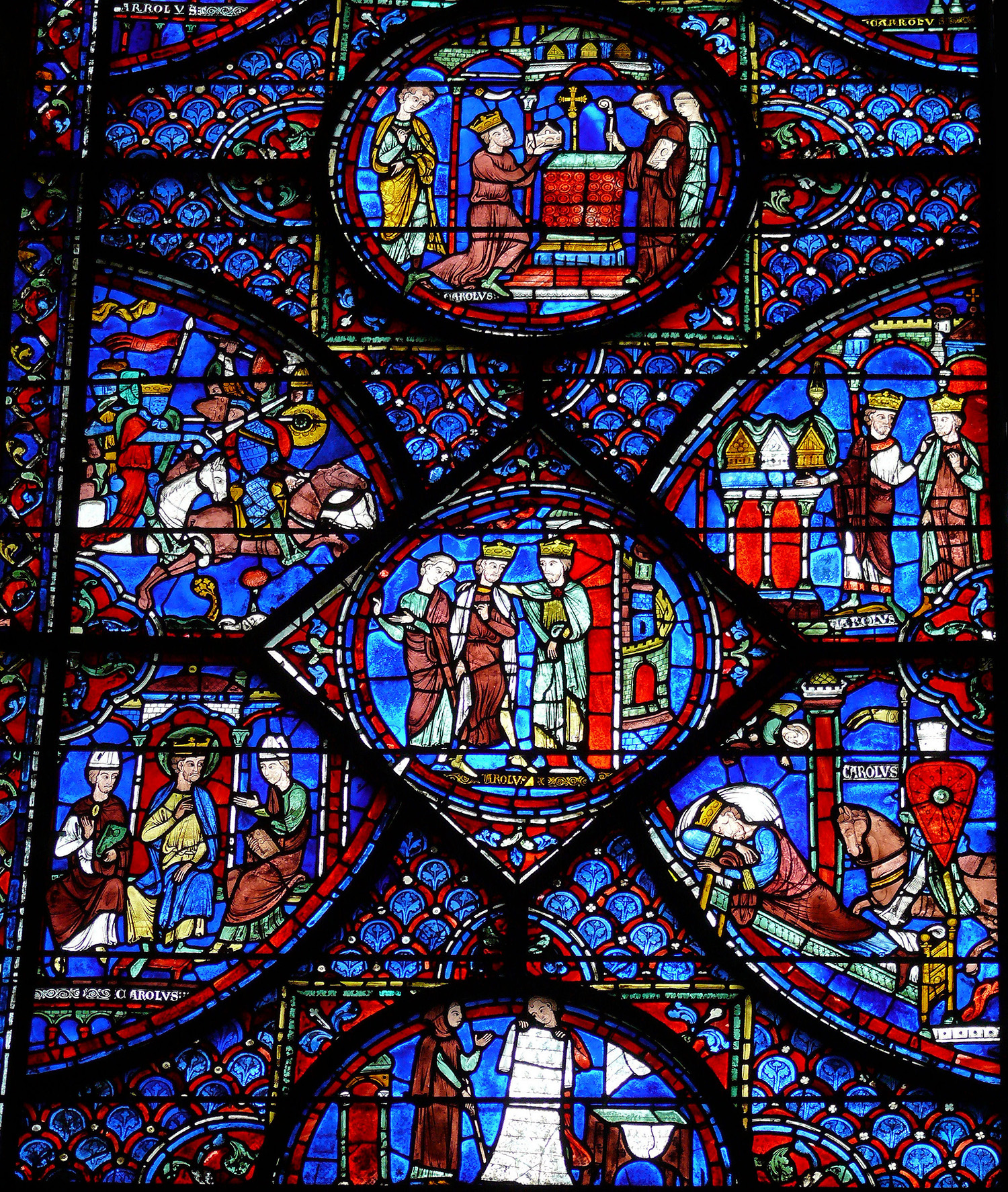

Today marks the feast day of Saint Charlemagne. The Frankish leader was canonized by the antipope Paschal III in 1165, some three-and-a-half centuries after his death on January 28, 814. Political motivations assuredly played a role in this act given the pontiff’s desire to curry favor with Charlemagne’s successor, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Yet it is well worth remembering that distinctly local commemorations of the emperor had already been established throughout the original footprint of the Carolingian empire.

Although Paschal III’s ordinances were officially revoked during the Third Lateran Council in 1179, Charlemagne remained a figure of veneration, particularly in the cathedral of Aachen, which houses an elaborate thirteenth-century shrine containing his relics. On Karlstag, the twelfth-century liturgical chant Urbs Aquensis, urbs regalis is performed within the cathedral in celebration of the emperor’s memory. With its vivid language, the sequence evokes Charlemagne’s accomplishments by describing him as a soldier of Christ, just ruler, converter of infidels, and an all-around rex mundi triumphator. Such descriptors complement posthumous medieval depictions of the emperor, which are amply represented in the Index’s catalogue. Portrayed variously as a ruler, warrior, patron, and saint in different media, these figures of Charlemagne underscore the diversity of guises and legends that developed after the historical emperor’s death.