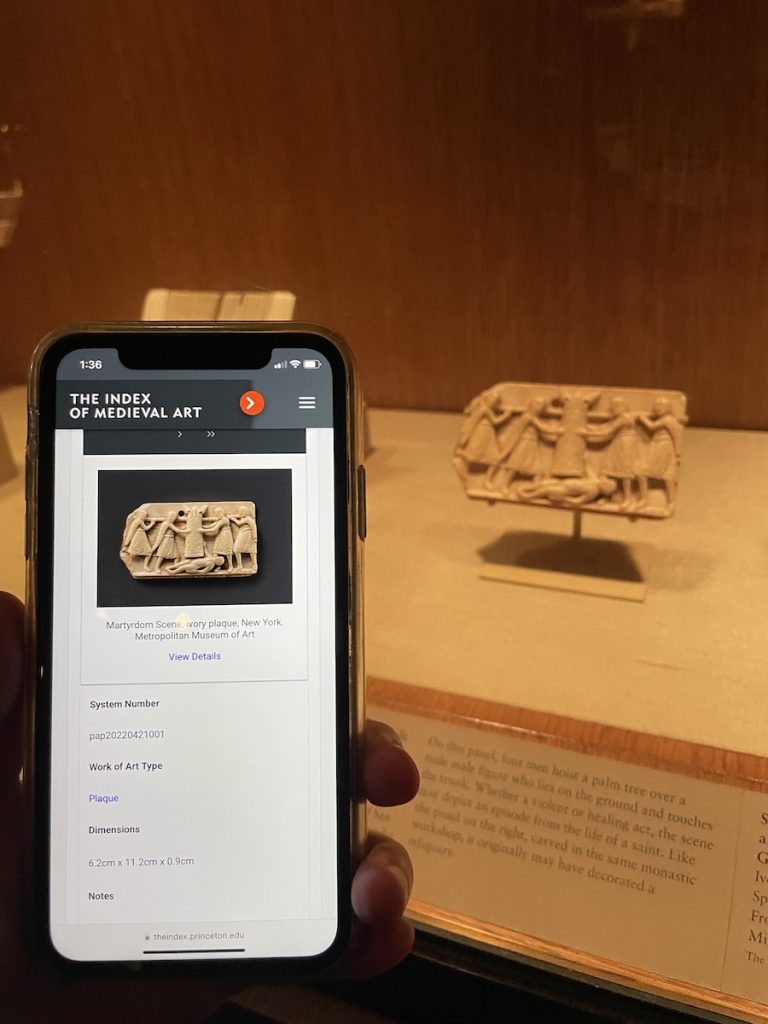

This summer the Index of Medieval Art achieved a milestone in our cataloging mission: the completion of all ivory objects in our print photo archive. In all, more than three thousand objects from the Index’s card catalog have been added to the Index database, significantly enhancing the online collection and establishing the Index as a more vital resource for the study of medieval ivories. The new records include chess pieces, croziers, caskets, combs, retables, diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, knife handles, mirror cases, oliphants, pyxides, statuettes, and much more! Many of the works of art date to the Gothic period, but late antique, early medieval, Romanesque, Carolingian, Siculo-Arabic, and Byzantine works are also well represented. The materials and techniques categorized as “ivory” were also surprisingly diverse, including carvings in walrus tusk, also known as morse, as well as in horn, bone, antler, and even a ceremonial staff made from narwhal tusk.1

The ivory cataloging project was begun shortly after staff returned to in-person work during the later stages of the pandemic. Index research staff worked from inventories of the photo files made by former student assistant Michele Mesi in 2019.2 Many of the photo files dated from the 1930s to 1950s, and they usually provided a subject and photograph with a bibliographic reference, though sometimes they included much less! Working from the clues left by earlier generations of Indexers, the current crew shared key publications and relied when possible on databases, such as the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project, to work through the records alphabetically by location and collection.3

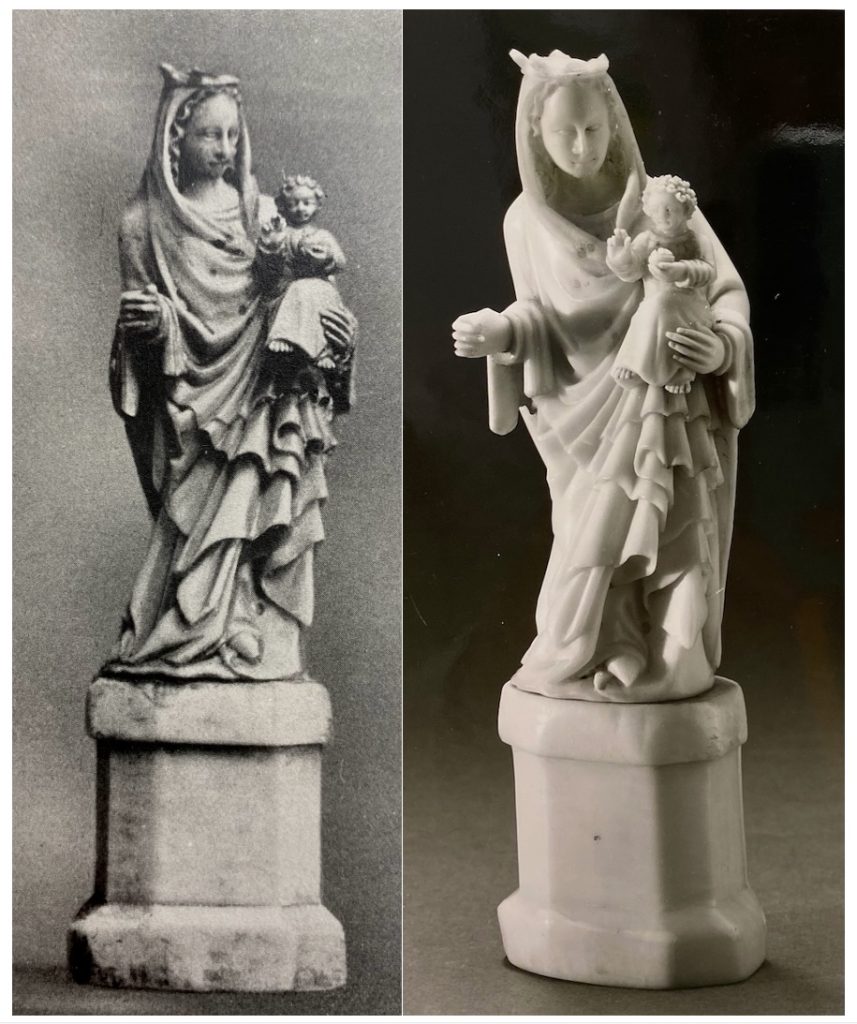

Sometimes we found research clues in unorthodox sources. While researching an early fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Fiore, Art History Specialist Jessica Savage found images shared by the Associazione di Festeggiamenti di Lugnano, Rieti on Facebook. According to the association’s website, the statue is mounted on a gilded decorative support and processed through the streets of Lugnano during the “Festa della Madonna del Fiore” every first Sunday of September.4 It was fascinating to see the medieval relic in celebratory use to this day, and it is just as easy to imagine the lives of these various objects as they were gifted, traded, used, venerated, and now discoverable online with the Index database–many digitized for the first time.

Many of the objects and fragments on which we worked had been dispersed either before or after their records were created, and some items or even whole collections had changed hands. Sometimes this provoked unexpected collaborations: in one case, Art History Specialist Maria Alessia Rossi cataloged the right wing of a diptych in the Musée de Cluny depicting the Coronation and Dormition of the Virgin, and then, about a year later, Savage found the other wing, with the adjoining scenes of the Last Judgment and Adoration of the Magi, separately cataloged in the file of the Paris Cabinet des Médailles. The diptych wings are now digitally reunited as Index System number mar20230306003.

Reflecting on the ivories project, Index Director Pamela Patton said, “One of the most exciting things about cataloging the ivory backfiles was the chance to bring elements of a single object that had been dispersed over time into a single work of art record, as for the Casket of Saint Emilianus (San Millán), a reliquary made in the eleventh century but damaged when the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla was sacked in 1089.” Some of the ivory plaques remain in the monastery, but others were dispersed to at least seven different museums in Europe and the United States. Patton recalled, “Bringing together images and metadata for all these works, including one plaque that was lost in World War II but preserved in a German photograph, was a very satisfying endeavor.”

Byzantine rosette caskets were another category that some researchers may find intriguing. Art History Specialist Henry D. Schilb created a record for the Hermitage Museum’s inv. no. Ѡ17, now Index System number hds20250128001, one of a group of similar caskets cataloged by the Index over the years, with examples in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (inventory number Kg 54:219, Index System number 77286) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (inventory number 1924.747, Index System number 77285). Known for the prominent use of rosette ornament, this group of caskets has also attracted the attention of no less eminent a scholar than Princeton alumnus Justin Willson, whose recent article discusses why we find among scenes of Adam and Eve the figure of Plutus holding a moneybag.5

New iconographic subjects encountered during our work on ivories were sometimes added to the Index database during cataloging. For example, the bust portrait of “Ulpia Sirica,” a second or fourth century woman from Rome, was discovered by Rossi in the ivory files. The only known depiction of Ulpia on this opus sectile-style plaque, made of marble, blue and green enamels, glass paste, and painted bone and ivory listels, was buried by a landslide in the late 1900s. Her portrait is last known to have been embedded in a Latin epitaph in the Catacombs of Saint Agnes in Rome; it is preserved in a late nineteenth-century watercolor by Salvatore Merola, kept in the diary of Ubaldo Giordani.6

Additionally, the little-known female saints “Oderade of Quedlinburg,” “Agnes II of Quedlinburg,” and “Pusinna, Saint” inspired new iconographic research by Art History Specialist Catherine Fernandez during her work on the Reliquary of St. Servatius now housed in the Stift Quedlinburg, Domschatz. The rarely depicted religious women, a prioress, abbess, and hermit, respectively, appear in an iconographic grouping, or relic list, with other saints on the bottom enamel panel of the Reliquary of St. Servatius. The ivory reliquary was made in Fulda or Metz around 870 with gem and metalwork additions ca. 1300.

The ivory cataloging project produced a new authority in the Style/Culture category. We added the heading “Forgery” to describe objects that, although executed in a “medieval” style, were actually—and often with deceptive intent—produced by more modern artists.7 The project also required the verification of a great many locations, part of Schilb’s ongoing project to make the location data used by the Index as accurate and precise as possible.

Indexers celebrated the completion of the ivories project with all staff at an in-house celebration that featured appropriately pale but delectable treats (popcorn, burrata, white chocolate-covered almonds, vanilla meringues!) and offered a chance to reminisce about highlights from the project.8 Many more ivory objects remain to be cataloged by the Index in years to come, but for now we are thrilled to make available online all the objects that have been cataloged by the Index to date. We acknowledge there might still be missing or outdated information on some of these records. Sometimes images could not be tracked down, current locations could not be verified, or works were presumed lost or destroyed. Our cataloging efforts will always be a work in progress, and we remain open to your corrections, suggestions, and questions.

Please reach out to us via email, and be sure to follow us here for all our latest updates. You can also find us on Facebook and Bluesky.

Please join us and register for the next virtual database tutorial with the Index on Tuesday, March 25, 2025 from 12:00 – 1:00 pm EST.

Read more about it at this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/index_training/.

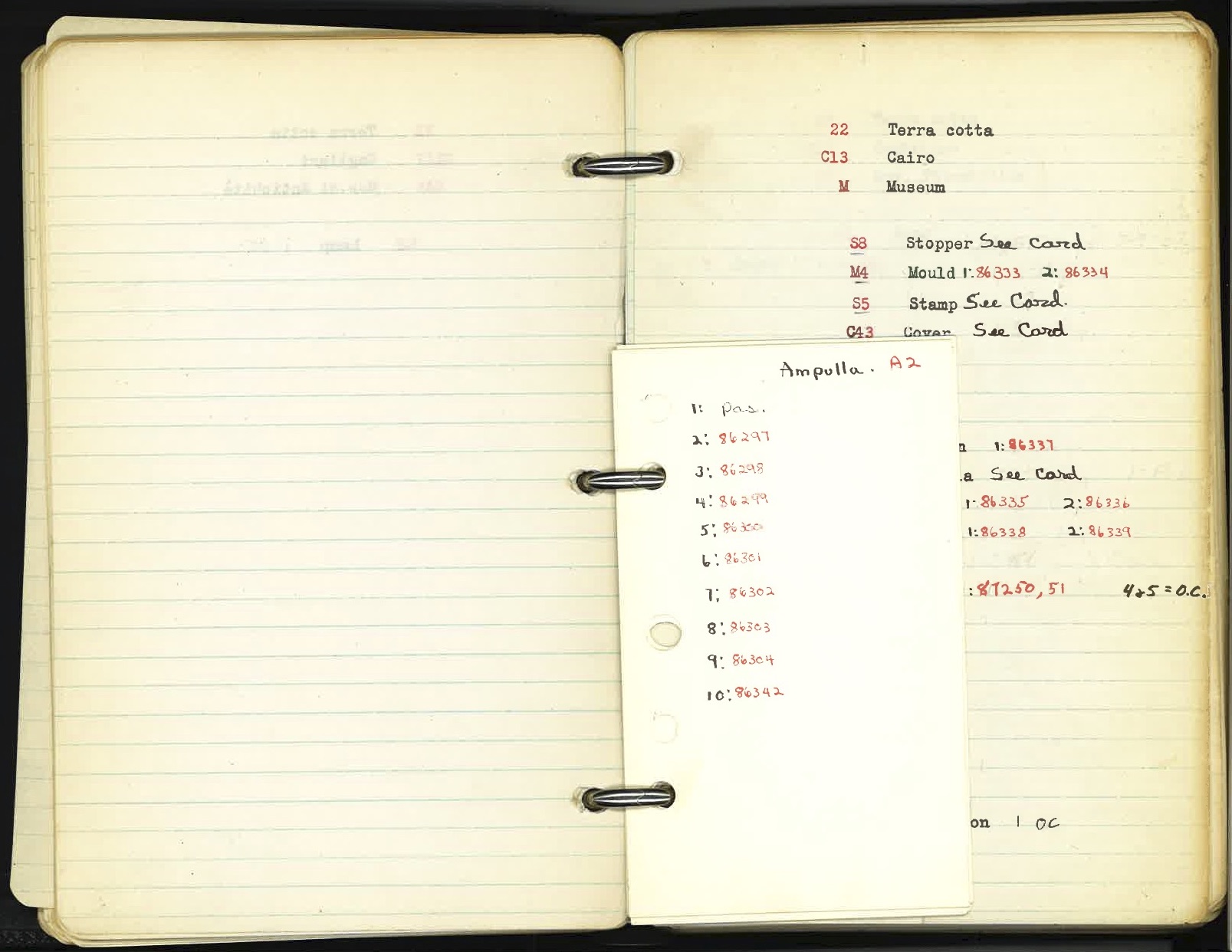

This summer The Index of Medieval Art welcomed two students from the Master of Information program at Rutgers University to inventory the Index’s photographic archive. Comprising nearly two hundred thousand cards in sixteen different medium categories, this historic image collection provides researchers a rich resource of sometimes rare visual references for the study of art produced throughout the Middle Ages. The inventories undertaken by Ryan Gerber and Michele Mesi have illuminated the extent of the archive and helped to assess the image and cataloguing needs for ongoing research and cataloguing at the Index. In this special two-part blog post, we are pleased to present their observations and accounts of their experiences.

It is a testament to the Index’s stimulating power that, despite my lack of an art-historical background, I found myself entranced by the system of cataloguing medieval iconography that the Index pioneered and is still practicing to this day. Its vision of greater accessibility through complete digitization represents another milestone in its long history, and one which will be a gift to scholars of all persuasions and experience levels.

A system largely developed by Index director Helen Woodruff in the 1930s, the photographic archive is organized in the first place by medium, then by location, object type, and the numeric order within that group. Unique codes on the left-hand corner of every index card in the catalogue represent each of these levels of organization. The fruits of this labor are hard to miss after spending any time with the Index and its elegantly interwoven subject index and photographic archive, where one can move seamlessly from subject description to pictorial representations and vice versa.

This work has also left behind a trove of archival resources such as hundreds of rolls of film and the so-called “Black Books” that were used to track the negative numbers. Each of the medium categories I inventoried not only laid the groundwork for further analysis of the collection as a whole, but highlighted the Index’s remarkable century-old ability to generate new curiosities and paths of inquiry.

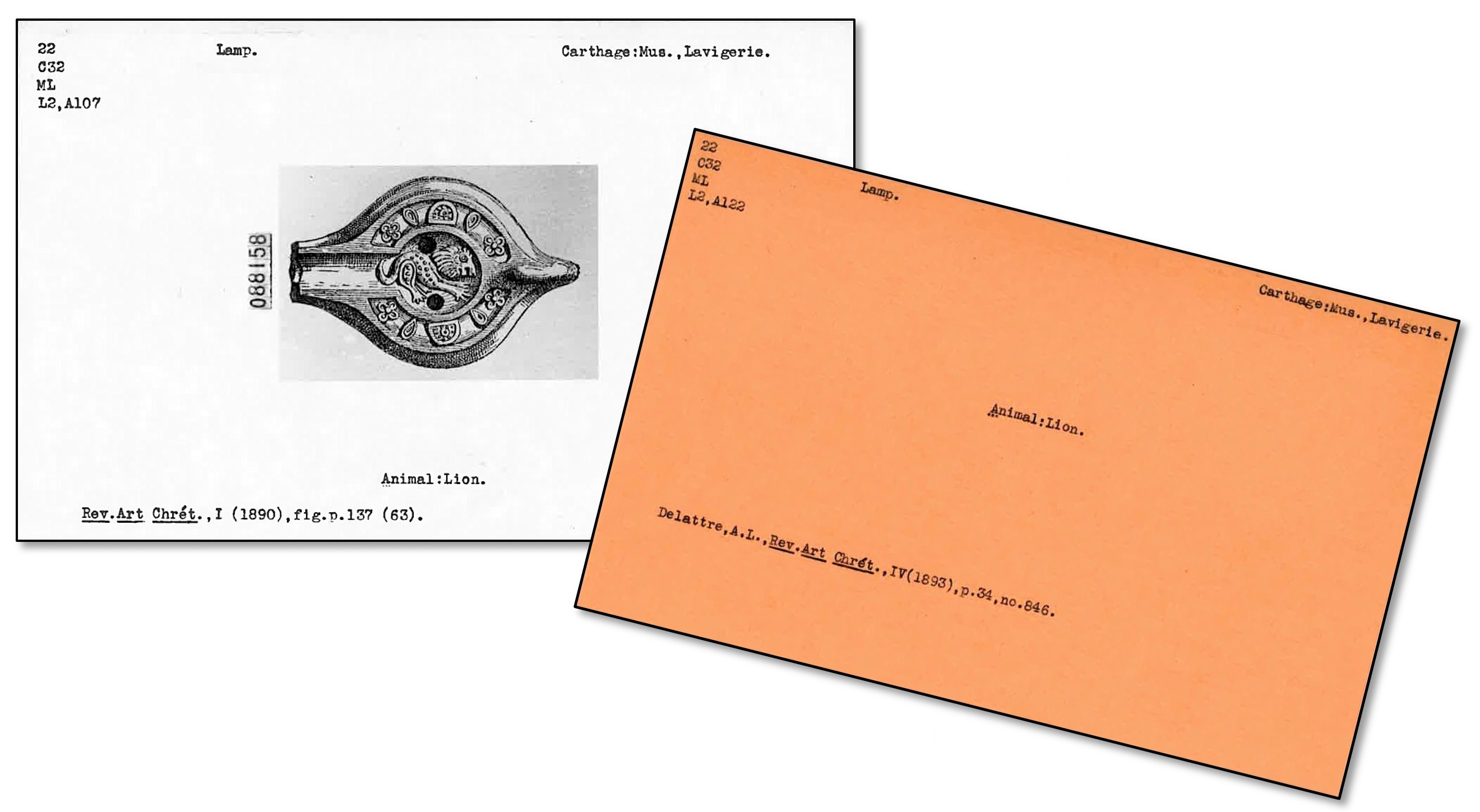

Terracotta, Temporary Cards, Lamps, and Lions

Under the medium “Terra Cotta”—a mixture of clay and water that is formed and baked or fired—the Index records more than twenty-five hundred objects across 196 locations. Of these objects, about sixty-five percent of them are oil lamps. The inventory of these files revealed some of the more common iconographic motifs found on terracotta objects, which include foliate ornament, a variety of land animals and birds, symbols such as crosses, as well as inscriptions and monograms. One terracotta lamp from the Benaki Museum in Athens depicts two of these popular motifs—a lion and a tree—combined on one impressed discus (Fig. 1).

Most photograph cards contain representations of the objects, but they also record the object’s location, the photograph’s negative numbers, subject headings for the image or images on the object, and some bibliographic information. However, there are many temporary “Orange Cards” in the archive that contain only a bibliographic reference and a subject term, and these still await corresponding images. Their inclusion in the original system nonetheless provides important data points about the objects they describe, laying the groundwork for future cataloguers to source the images for these object records. For example, the Index’s photo archive of terracotta objects in the National Museum at Carthage is mostly Orange Cards because the original Index records of these objects derive from a 19th-century publication with very few illustrations. While it would be useful to see images of the “lions” held at the National Museum in Carthage, even in the absence of photographs it may be just as useful to know that, of the 970 terracotta lamps held in that location, nearly four hundred depict animals, and about sixty-five of those include a lion.

A Face in Gold Glass

The “Gold Glass” files record over 650 objects across sixty-three locations dating mostly from late antiquity between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Of these objects, nearly half are vessels of some kind. Gold glass developed as a medium in the ancient Roman and Hellenistic periods and consisted of decorative engravings made in gold leaf, which were then sandwiched between fused layers of glass. The result was lavish decoration, and exemplary pieces in this medium offer strikingly detailed portraits of their subjects, often depicting married pairs, family groups, or religious figures associated with one another, such as Saints Peter and Paul. Historians have noted the rarity of gold glass, as well as its costly, specialized method of production.[1]

Gold glass was a special interest of Index founder Charles Rufus Morey, and his pioneering catalogue of the Vatican Library’s collections features as its first entry an example also catalogued by the Index. It shows the busts of a married couple inscribed above with the name Gregori and a Latin equivalent of “cheers!”: “Gregori bibe [e]t propina tuis,” or “Gregory, drink and drink to thine!” (Fig. 2).[2]

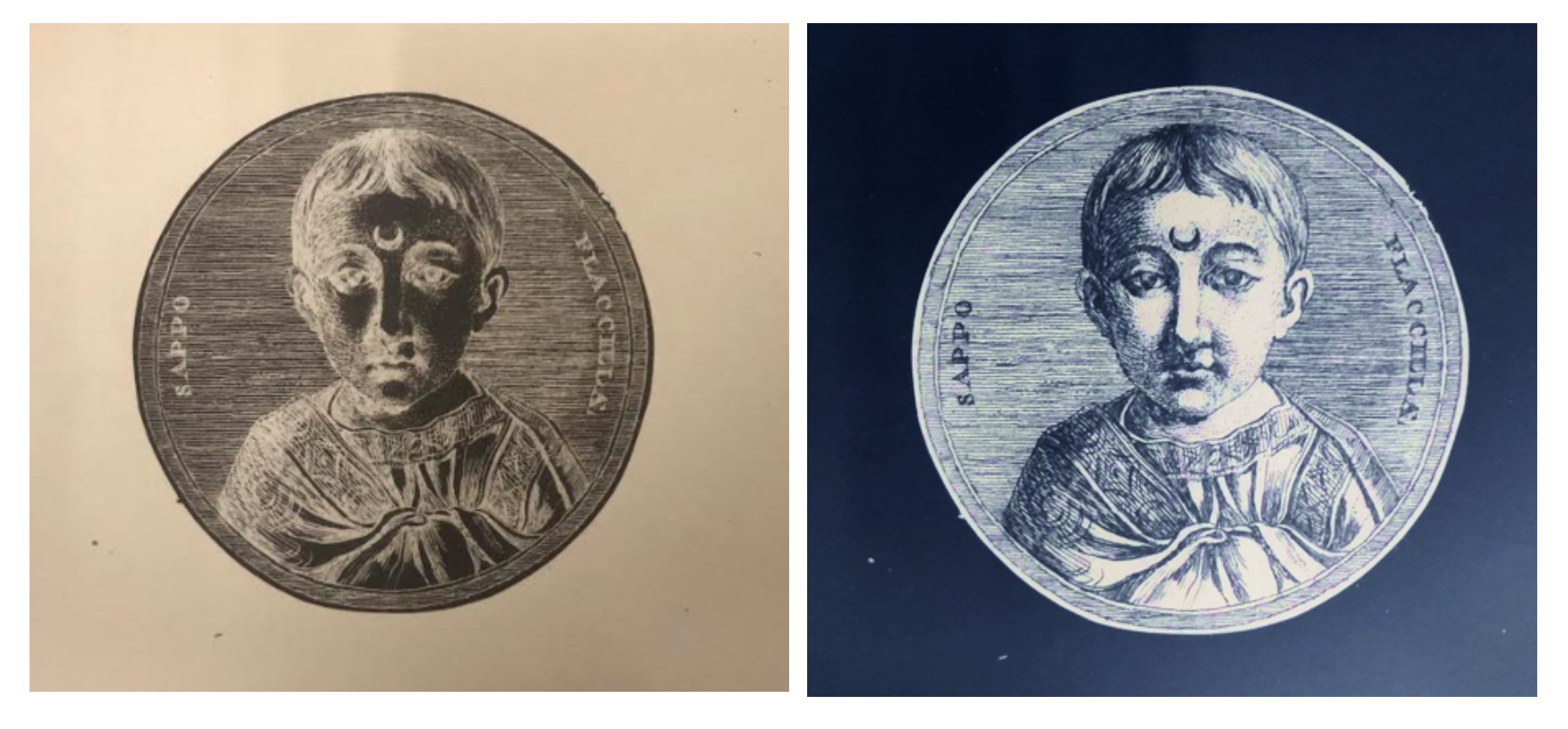

Another interesting discovery in the “Gold Glass” category was a round vessel fragment last recorded in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. It depicts a striking bust of a figure with shorn hair, dressed in a trimmed tunic, and with a distinctive crescent shape on their forehead. The only other information on the photograph card was the source of the image, the antiquities catalogue that Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus published in seven volumes from 1756 to 1767.[3] Caylus’s catalogue was a valuable starting point for identifying this figure, whose iconographic description had not been entered in the Index’s subject files or the database. A little more searching led to a color image in a French catalogue, the Histoire de l’art de la Verrerie dans l’Antiquité (Fig. 3), and to the conclusion that the inscription “SAPPO FLACILLAE”—with the genitive form of the empress’s name—referred to a branded enslaved person who had been freed by the Roman Empress Aelia Flacilla (356–386). We also used the photo-editing web application Pixlr to create a positive image of “Sappo” so that the image from the Index archive can now be seen as it appeared in the catalogue of the comte de Caylus (Fig. 4).

Impressions in Wax

Comprising a little over one thousand objects in 105 locations, the “Wax” medium files are overwhelmingly made up of stamps from Europe dating largely to the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the archive groups these objects into the single object category “Stamp,” the Index database divides them into two Work of Art Types, “Seal Matrix” (that is, the tool used to make the impression) and “Seal Impression” (that is, an impression made by a matrix).[4] Viewing about a thousand examples of Gothic seals intended for both religious and secular officialdom brought into literal relief the development of the production of seal dies from simple figural representations to complex ecclesiastical chapters in miniature, such as the Stamp of Ely Priory, dated to about 1240–1260 (Fig. 5). Other favored subjects in wax seals include heraldry, nobles, and popular saints and bishops, like Thomas Becket. The wealth of iconographic information in the “Wax” files—indeed throughout the archive—emphasizes that the Index is not a closed system, and has at every turn great potential for leading one into new areas of inquiry.

Ryan Gerber is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. He holds an MA in English from The College of New Jersey with a concentration in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. His interests include digital preservation and retrieval, the digital humanities, and information behavior.

See Part 2 written by Michele Mesi.

[1] Giulia Cesarin, “Gold-Glasses: From their Origin to Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean,” in Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–45.

[2] Morey noted of the inscription that “the E of ‘bibe’ or of ‘et’ [was] omitted by mistake.” Charles Rufus Morey, The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1959), 1. Translation after Georg Daltrop in Leonard von Matt, Georg Daltrop, and Adriano Prandi, Art Treasures of the Vatican Library (New York: Abrams, [1970]), 168.

[3] Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1756–57), 193–205, pl. 53.2, https://archive.org/details/recueildantiquit03cayl/page/n10.

[4] See the Index database Work of Art Type browse list to access these Work of Art References.

Precious Gems Containing a Wealth of Iconography

“Glyptic” is among the smaller medium categories in the Index archive, filling only one drawer with a little more than eleven hundred cards that record only about nine hundred objects. The term “glyptics” refers the art of carving gems or seals—whether in intaglio or in relief—typically in gems or precious stones such as jasper, agate, carnelian, and amethyst.[1] This form of art is one of the oldest—known since the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Assyrian civilizations—but it was not until the Hellenistic period that relief cameos, seals, and more intricate glyptic objects began to appear.[2]

Glyptics, which were often worn as jewelry or incorporated into ecclesiastical objects, are recorded in the Index primarily as gems, amulets, plaques, rings, and stamps, and the largest category, cameos, which makes up nearly a third of the glyptic objects in the Index files. A significant portion of the subjects on these carved gems include animals and plant life, like doves, dolphins, fish, palm trees, and fantastic creatures. There are other symbols as well, such as the anchor, which appears on over forty examples. A significant number of glyptics incorporate classical and mythological figures, such as Orpheus, Diana, Jupiter, and Hecate. Nearly twenty cards for gem objects record the Gnostic figure Abrasax (Fig. 1). Glyptics such as these were powerful talismans for their owners.

The traditional use of spiritual amulets was also adopted by Christians using Christian symbols and themes.[3] Christian iconography on glyptics include the triumphant Archangel Michael or Saint George, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and the Good Shepherd. One cameo of opaque black glass made in the 13th century depicts Saint Theodore transfixing the dragon and well represents the preference for saintly imagery on later cameos (Fig. 2).[4] The inventory also revealed that there were nearly thirty examples of incised depictions of monograms on glyptics with a third of them being the Chi-Rho, a symbol for Christ consisting of the first two letters of the word “Christos” (Christ) in Greek.

The major collections represented in this medium include the Staatliche Museen in Berlin (over eighty objects) and the British Museum in London (nearly 125 objects. However, a large number of glyptics (over 140 objects) are recorded as “Location Unknown,” these items having been entered into the Index from major publications that did not provide the precise location at the time of publication.

Radiant Ivories for Both Secular and Religious Narratives

With nearly forty-seven hundred cards covering a little over thirty-one hundred objects, Ivory represented a more extensive category in this inventory project. The types of ivory objects recorded by the Index range from plaques, chess pieces, croziers, and triptychs to the more unusual oliphant (or hunter’s horn) to the handles of various utensils, and even a saddle. Some of the major collections represented in this medium are the Musée du Louvre and the Musée de Cluny in Paris, and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Ivory objects were expertly carved in minute detail, usually from the tusks of elephants. In the Index database, ivory acts as a “parent medium,” an umbrella covering such materials as bone, walrus tusks, and antlers.[5]

Various motifs of courtly love were often depicted on ivory caskets, plaques, mirror cases, combs, and other fine domestic objects.[6] A preference for secular subjects on ivories emerged in the twelfth century when an influx of secular imagery was brought to Europe from the Middle East after the Crusades, as well as through a rise in vernacular literature, legends, and romances.[7] Entertaining stories such as the tale of the Virgin and the Unicorn provided plenty of thematic material to adorn precious ivory objects. They often offered a double meaning or moral lesson, as in the story of Tristan and Isolde depicted on an early 14th-century ivory casket now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which warns against temptations of lust (Fig. 3).[8]

Despite their popularity, secular ivories are fewer in number than devotional works of art in ivory. Roughly a quarter of the ivory objects recorded in the Index are representations of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. This figure rises to more three quarters when we add individual figures of Christ or the Virgin Mary. One type seen rather frequently is that of the Virgin nursing the infant Christ—known in Latin as the Virgo Lactans—which the Index categorizes among the many “types” of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. In the database, the subject heading Virgin Mary and Christ Child, Suckling Type is attached to over 290 Work of Art records. More than forty of these are ivory. This Virgo Lactans iconographic type is exemplified by a 14th-century ivory statuette in the Yale University Art Gallery, which displays an intimate and lifelike relationship between mother and child (Fig. 4). Thus, the devotional message is made personal.

The Project Continues …

Encompassing eight drawers of roughly one thousand cards each, “Painting” proved to be an abundant medium, but “Illuminated Manuscript” is by far the largest medium category in the Index, filling fifty-six of the photograph drawers. Medieval art objects encountered in these two categories range from painted icons and altarpieces to a wide variety of liturgical manuscripts and other illuminated books numbering perhaps in the thousands. The inventory of these and other remaining categories—including those comprising in situ works of monumental art, such as “Mosaic” and “Fresco”—will continue after this summer.

As a “living archive” that covers more than a millennium of artistic creation, the Index of Medieval Art has always been improved and expanded by the interactions of the cataloguers who create it with the with researchers who use it. Creating these inventories has been an illuminating way to participate in that process and to learn more about the contents of the Index card catalogue being prepared for entry into the online database. This project was challenging at times, due to the sheer breadth of the paper files, but it has been an invaluable undertaking for the ongoing process of research and digitization, and will improve accessibility to the records contained in this century-old archive of medieval art.

Michele Mesi is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. From Rutgers University, she also holds a Bachelor’s degree in English with studies in Art History and in Digital Communication, Information, and Media. Her interests include art conservation, archival processing, and working with rare books and manuscripts.

See Part 1 written by Ryan Gerber.

[1] The Index of Medieval Art follows the standards for material description established by the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). See the Art & Architecture Thesaurus® Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/.

[2] O. Neverov and A. Durandin, Antique Intaglios in the Hermitage Collection (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1976), 7.

[3] Neverov and Durandin, Antique Intaglios, 8.

[4] The Index records the iconography in question as Theodore Tyro or Theodore the General, Slaying Dragon.

[5] See the glossary entry on the Index database Medium browse list for “ivory.”

[6] J. Lowden and J. Cherry, Medieval Ivories and Works of Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Art Gallery of Ontario, 2008), 122.

[7] R. H. Randall, “Popular Romances Carved in Ivory,” in Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1997), 63.

[8] Randall, “Popular Romances,” 67–68.

The ways in which scholars research the iconographic traditions of the Middle Ages is continuously evolving. In order to address this, the Index of Medieval Art organized and sponsored a roundtable, Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods, at the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. The five panelists briefly presented on the ways in which they incorporated iconography into their teaching, research, and curatorial work. They then participated in a discussion of how they use and develop online resources, such as image databases, to reach students and researchers. The result was a lively dialogue about how digital approaches can make medieval iconographic study more accessible to a diverse, global audience.

One of the first topics of discussion was the avenues by which viewers encounter medieval iconography in the twenty-first century. Anne Stanton, Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Missouri, raised the point that popular social media outlets and online databases are often the first portals through which many students gain access to medieval images and learn about subject matter in works of art. Many institutions have responded to this this fact by using social media platforms to broaden interest in iconography and connect users to works of art. The many vibrant examples of social media use in the field, ranging from museums to libraries, include the Getty, Dumbarton Oaks, and the British Library. Sabine Maffre, Curator of the Mandragore Database at the National Library of France, discussed developments at the library’s blog Gallica, which has been inviting professional bloggers to write posts about illuminations in order to diversify their audience and make their medieval image collections more visible.

Beyond questions of access, another change has occurred in the ways in which we think about iconography. Konstantina Karterouli, postdoctoral fellow and graduate of Harvard University, presented an Artificial Intelligence (AI) project that the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection is developing with the goal of teaching computers to recognize the different architectural elements of a medieval building. Commenting on the wider potential of this approach, Maffre also noted that the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) staff have been working toward implementing automatic recognition of manuscript illuminations through AI. A contrasting approach to iconography, presented by Isabelle Marchesin of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) at the Sorbonne in Paris, faces head-on the problem of offering something that AI still cannot provide: interpretations of specialized content. The OMCI (Ontology of Medieval Christianity in Images) project, founded and developed by Marchesin, is based on the concept that, beyond narrative and portraits, Christian medieval images implicitly refer to another level of signification that is ontological and strongly connected in this case to theology as a holistic system of explanation of the world.

One important takeaway from the roundtable was the recognition that the role of the iconographer itself is changing. As Professor Marina Vicelja of the University of Rijeka emphasized, rather than requiring the solitary work so often undertaken in the past, it could and should be seen in light of collaborations, interdisciplinary research, and international networks. A starting point could be the implementation of cross-discoverable databases, shared standardized vocabularies, and the use of platforms like Biblissima, a digital library and widely interoperable data cluster designed to gather and give access to the main iconographic and textual databases. These ideas inspired discussion of the difficult balance between the strategies used by database specialists and the kinds of usability expected by twenty-first century researchers. Karterouli strongly emphasized the importance of standardization in these endeavors to help retrieve information, and Vicelja stressed the necessity of integrating metadata in order to avoid misunderstandings.

In the twenty-first century, we find ourselves at a crossroads between traditional methods of iconographic study and the implementation of pioneering technologies such as AI. The potential for interoperable platforms to enhance the research experience could answer new expectations with new possibilities. While it can be difficult to strike a balance between time-tested approaches and new ideas, the tension is proof that the study of iconography is very much alive and evolving. We hope that the Index roundtable at Kalamazoo was only the first word in a vibrant and expansive dialogue among an international community of creators and consumers of information about medieval iconography.

Going to Kalamazoo this year? Ever wanted to learn more about the impact of digital tools and methods on medieval art research? Be sure to circle your programs for two exciting sessions on current topics in iconography, a roundtable and a workshop, co-organized by Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage of the Index of Medieval Art.

I. Saturday, May 11 at 10:30am [Session 346]

Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods (A Roundtable)

Stemming from the launch of the new database and enhancements of search technology and social media at the Index of Medieval Art, this roundtable addresses the many ways we encounter and access medieval iconography in the 21st century. Our five participants will speak on topics relevant to their area of specialization and participate in a discussion on how they use online resources, such as image databases, to incorporate the study of medieval iconography into their teaching, research, and public outreach.

Digital Information and Interoperability: Facing New Challenges with Mandragore, the Iconographic Database of the BnF

Sabine Maffre, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Ontology and Iconography: Defining a New Thesaurus of the OMCI at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris

Isabelle Marchesin, Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA)

Iconography at the Missouri Crossroads: Teaching the Art of the Middle Ages in Middle America

Anne Rudloff Stanton, Univ. of Missouri

Medieval Iconography in the Digital Space: Standardization and Delimitation

Konstantina Karterouli, Dumbarton Oaks

Online Resources in the Changing Paradigm of Medieval Studies

Marina Vicelja, Center for Iconographic Studies, Univ. of Rijeka

II. Sunday, May 12 at 8:30am [Session 505]

Lost in Iconography? Exploring the New Database of the Index of Medieval Art (A Workshop)

This workshop will demonstrate how to get the most out of the new Index of Medieval Art database by using advanced search options, filters, and browse tools to research iconographic subjects. A short presentation will introduce the new subject taxonomy search tool that will further facilitate exploration of the online collection.

We look forward to an invigorating discussion on current issues in iconographic research and to sharing an update on the new database. You can find out more about the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, held from 9-12 May 2019, including the full schedule here.

54th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, MI, May 9 to 12, 2019

Sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University

Organizers: M. Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage (Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University)

Stemming from the launch of the new database and enhancements of search technology and social media at the Index of Medieval Art, this roundtable addresses the many ways we encounter medieval iconography in the twenty-first century. We invite proposals from emerging scholars and a variety of professionals who are teaching with, blogging about, and cataloguing medieval iconography. This discussion will touch on the different ways we consume and create information with our research, shed light on original approaches, and discover common goals.

Participants in this roundtable will give short introductions (5-7 minutes) on issues relevant to their area of specialization and participate in a discussion on how they use online resources, such as image databases, to incorporate the study of medieval iconography into their teaching, research, and public outreach. Possible questions include: What makes an online collection “teaching-friendly” and accessible for student discovery? How does social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and blogging, make medieval image collections more visible? How do these platforms broaden interest in iconography and connect users to works of art? What are the aims and impact of organizations such as, the Index, the Getty, the INHA, the Warburg, and ICONCLASS, who are working with large stores of medieval art and architecture information? How can we envisage a wider network and discussion of professional practice within this specialized area?

Please send a 250-word abstract outlining your contribution to this roundtable and a completed Participant Information Form (available via the Congress Submissions website: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) by September 15 to M. Alessia Rossi (marossi@princeton.edu) and Jessica Savage (jlsavage@princeton.edu). More information about the Congress can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress.