By Jove! This year a special planetary alignment will occur on December 21st, also the Winter Solstice, when earth’s northern pole is at its greatest tilt away from the Sun. During this “Longest Night,” the planets Saturn and Jupiter will be within a tenth of a degree to one another, appearing to form a single “star.”

While an alignment of Saturn and Jupiter happens about every 20 years, when it happens in 2020 it will be one of the closest alignments of these two planets for over 800 years, and by some accounts since the year 1226.[1] The 1226 Saturn-Jupiter conjunction coincided with several historical milestones. In France, the reign of Louis IX, the only French king to be canonized by the Catholic Church, began following the death of his father Louis VIII. In Norway, the cleric Brother Robert translated the popular chivalric romance of Tristan and Iseult into Old Norse at the request of King Haakon IV. In the Kingdom of Georgia, the Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, last ruler of the Khwarezmian Empire, captured Tbilisi in the Battle of Garni. The mendicant friar, preacher, and later saint Francis of Assisi died on October 3rd. And according to Canadian astronomer and historian Vibert Douglas, the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan abruptly ended his military campaign in China, possibly owing to the phenomenon of five separate planetary conjunctions over the years 1226 and 1227.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the seven “planets”—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, and the sun and moon—were important celestial bodies in the heavenly realm. Each was thought to have a distinctive personality, an idea still reflected in Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets, composed between 1914 and 1916. Holst calls Jupiter “The Bringer of Jollity” and Saturn—colloquially also known as “Father Time”—“The Bringer of Old Age.” These names doubtless influenced the artistic expression in the series of dance performances for Holst’s Planets by the Princeton University Ballet in 2018 linked above.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, was initially named after the ancient Roman god of thunder, and its planetary neighbor Saturn, the god of agriculture and harvest, was also Jupiter’s father. In Greek mythology they are Zeus and Cronus and were sometimes represented by medieval artists as luminous pointed stars, or solid spheres in concentric circles of earth-centered astronomical diagrams, as in this later copy of a Byzantine geocentric model of the cosmos (Fig. 1).

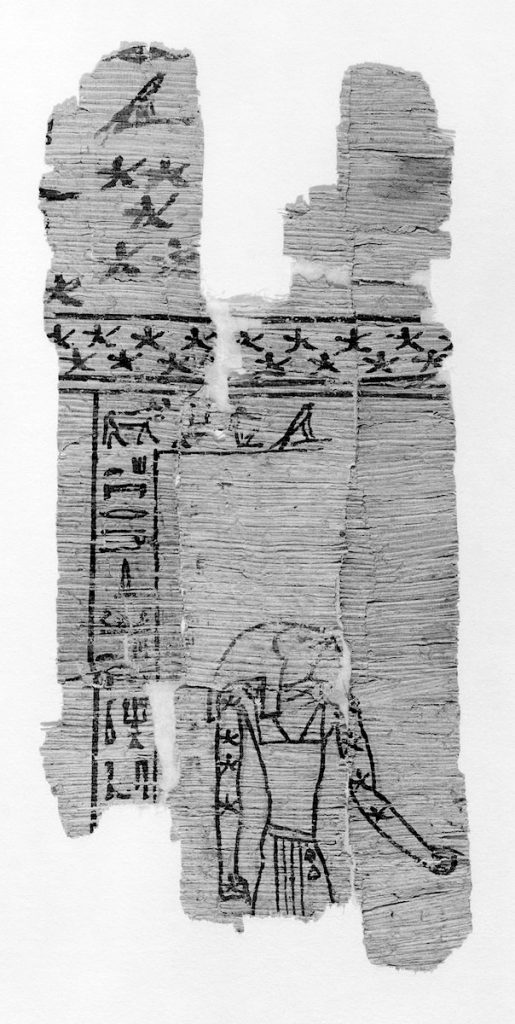

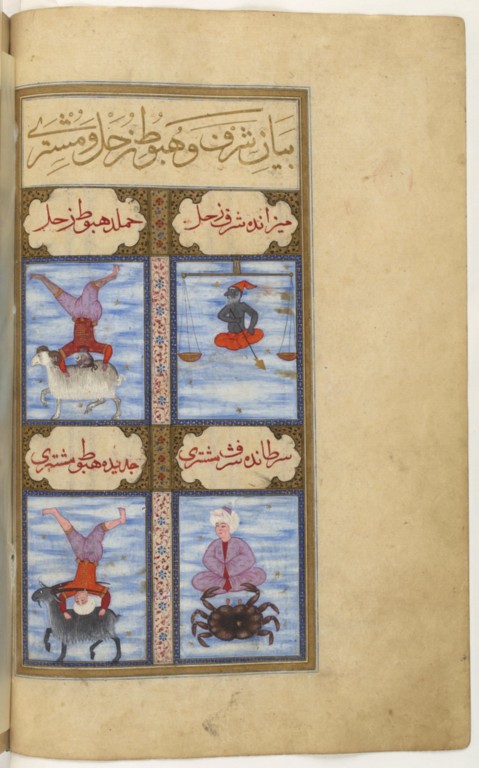

Representations of the planets are found in the artistic traditions of many cultures in which astronomy was an important science, including the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hellenistic, Indian, Byzantine, Islamic, and Chinese spheres. A possible early figuration of the planet Saturn can be seen on this ancient papyrus fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an Egyptian deity (Fig. 2). A much later figuration of the planets is found in this sixteenth century “Book of Felicity” (Matali’ al-saadet) made for Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595), now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which contains images of the “exaltation” and “dejection” of the planets—that is, when they are in apogee and perigee (Fig. 3). On folio 33v, Saturn’s exaltation in Libra is represented by the zodiacal scales, and his dejection in Aries shows him falling headfirst onto the back of a ram. The lower two vignettes similarly depict Jupiter’s exaltation in Cancer by pairing him with the zodiacal crab, and his dejection in Capricorn by tumbling onto a goat.[3]

In western European art, the planets were presented both as heavenly bodies and in symbolic form. In this late medieval manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“The Lover’s Confession”) by John Gower, a small miniature of the planetary system, prefacing the part on Astronomy, contains the sun and moon with human faces among five gold and starry planets, the uppermost two labeled with their Latin names “Saturnus” and “Iubiter” (Fig. 4).

In Dante’s Divina Commedia, the spheres of heaven were represented by planets; Saturn was the seventh sphere and Jupiter the sixth. In this illustration of Paradiso 22, the scene of the “Heaven of Saturn” is portrayed by Beatrice and Dante welcoming five nude souls descending a ladder from a glowing red star with seven points (Fig. 5). Reading the Paradiso, we know that this level of heaven was reserved for the contemplanti, or the founders of monastic orders, “men who were kindled by that heat which brings to birth the blessed flowers and blessed fruits.”[4]

In other medieval works the planets of the cosmos (and sometimes their children!) were personified as human figures.[5] In some of the earliest examples, planets were depicted as crowned figures, triumphant generals, or wearing laurels, rayed headpieces or wings; such types appear on Roman coins and as bust-length personifications in illustrated poems known as carmina figurata.[6]

Some representations evoked the temperaments often associated with each planet. Associated with the ambivalent nature of melancholy, Saturn was often configured as an old man with a handheld sickle (or a more “modern” scythe) and with a cloak draped over his head, but he can also hold a shovel, a wheel, and small nude figure, which he raises up as if to devour, a reference to the Greek myth in which he swallowed his children.[7] Jupiter was seen as a protective deity: his iconography varies from the classical, bearded archetype of “Zeus Pater” (Zeus the Father), who brandishes lightning bolts, a celestial wheel, or other symbols of his power, to his personification as a bishop in a late fifteenth-century astronomical miscellany in the Getty Museum.[8]

In classical mythology it was held that Jupiter drove Saturn away from his celestial throne. A marginal scene in this ninth century Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen depicts this dramatic argument of the ancients (Fig. 6). Saturn is pursued by Jupiter both wielding an axe, illustrating the First Invective against Julian the Emperor, “… let Jove rebel against Saturn, following his sire’s example; that sweet stone and bitter slayer of tyrants …”[9] In an early eleventh century manuscript of Rabanus Maurus’s encyclopedic De Universo, one miniature depicts Saturn with a scythe, nearly as tall as he, and Jupiter holds a symbolic pair of attributes: an eagle for deified justice and a serpent representing the age-old struggle for it (Fig. 7).

Two highly emblematic representations of the planets Jupiter and Saturn appear in the Rheinish manuscript of the Von Dem Gang des Himmels und Sternen (“The Course of the Heavens and Stars”), forming its own “planetary conjunction” at the close of the book (the miniatures are on facing pages). Both planets, Saturn personified as a simple farmer and Jupiter as city patrician, are decorated with imagery from a number of astrological and zodiacal sources, including their corresponding symbols for Libra and Cancer (Figs. 8 & 9).

The Index of Medieval Art database includes much more in the way of celestial imagery, including subjects related to the iconography of the other planets, stars, zodiac symbols, and constellations. The database also can be keyword searched for other named astronomical objects, such as “Star of Bethlehem.” These examples appear in a wide variety of works of art, including almanacs, calendars, astrological treatises, constellation maps, zodiac cycles, and a variety of narrative and allegorical works, and across different media, cultures, and periods.

The planetary motions of Saturn and Jupiter have been described by astronomers, such as Newton, Kepler, and Laplace, as “The Great Inequality,” meaning that while Jupiter’s mean period of motion is continually increasing, Saturn’s is continually diminishing and falling further behind.[10] Thus, both planets have long been approaching each other in the same direction, yet with enormous discordance.

The year 2020 has had its own prelude of tumultuous moments leading up to this great planetary conjunction. As the globe still grapples with a challenging year, it’s easy to imagine this alignment of Saturn and Jupiter as a sort of “clash of the titans,” but when we look west in the sky just after sunset, let us recall that this special occurrence, a most rare ballet of the planets, also marks a new season that will bring more light to our days.

[1] O’Neill, Mike. “Don’t Miss It: Jupiter, Saturn Will Look Like Double Planet for First Time Since Middle Ages.” SciTechDaily, 23 Nov. 2020, https://scitechdaily.com/dont-miss-it-jupiter-saturn-will-look-like-double-planet-for-first-time-since-middle-ages/; Strickland, Ashley. “Jupiter and Saturn Will Look like a Double Planet Later This Month.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/03/world/jupiter-saturn-conjunction-2020-scn-trnd/index.html; Levenson, Michael. “Jupiter and Saturn Head for Closest Visible Alignment in 800 Years.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Dec. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/06/science/space/jupiter-saturn-align-christmas-star.html.

[2] Douglas, A. Vibert, “Historical Significance of Five Conjunctions, 1226–27,” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 65 (1971): 129–132.

[3] See also this exquisite engraved and inlaid brass tray with personifications of planets made by Mamluk craftsmen and commissioned by a Sultan in Yemen in the early fourteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.1.60). For more on astronomy and astrology in the medieval Islamic world, see this essay by Marika Sardar: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astr/hd_astr.htm.

[4] Paradiso 22, 47–48 accessed at Barolini, Teodolinda. “Paradiso 22: Controlled Orphism.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2014. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-22/. See also the Princeton Dante Project https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/, with recent news and developments on the project here, https://humanities.princeton.edu/2020/11/29/2020-rapid-response-grant-literary-visualizations-reconstructs-imaginations-of-dantes-readers/.

[5] Discussion of the planets and their characteristics, temperaments, and affinities are found in many almanacs, planet books, and other cosmological treatises. See especially the classic Warburgian study by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (London: Nelson, 1964). Reissued by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

[6] The Index database records three examples of planetary carmen figuratem, all in the British Library, MS. Cott.Tib.B.V (fol. 44v), MS. Cott.Tib.C.I (fol. 33r), and MS. Harley 647 (fol. 13v).

[7] Klibanksy, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 197.

[8] For the Jupiter-Bishop on horseback see Getty Museum, MS. Ludwig XII 8 (83.MO.137), fol. 49v. See also the Art Stories post by Bryan C. Keene, “Written in the Stars: Astronomy and Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts,” Getty Iris Blog (30 April 2019), https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/written-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-astrology-in-medieval-manuscripts/.

[9] See lines 120–121: Gregory Nazianzen, “Julian the Emperor” (1888). Oration 4: First Invective Against Julian. The Tertullian Project, 14 Dec. 2020, http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_nazianzen_2_oration4.htm.

[10] Wilson, Curtis, “The Great Inequality of Jupiter and Saturn: From Kepler to Laplace,” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 33, no. 1/3 (1985): 15–290.

Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment Christ died, darkness swept over the land for three hours (Matthew 27:45). The foreboding skies at Christ’s crucifixion were also recorded in Luke 23:44-45 and Mark 15:33. Mark’s account, thought to have been written around the year 70 CE, was likely the earliest.[1] Some scholars have reasoned that this midday phenomenon was an actual eclipse, because the passage in Luke reports that darkness fell over the land when “the sun was eclipsed” (“τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος”) (Luke 23:45). However, the passage is usually translated “the sun was darkened.” The verb is in the passive voice, as is the verb “ἐσκοτίσθη” used in other versions of the Greek text, and both words can mean “was darkened” or “was obscured.”[2] No matter how we may interpret the words relating the phenomenon, and no matter whether it is possible to attribute the darkness thus described to a real astronomical event, scriptural hours of daytime darkness over Golgotha presented an iconographic opportunity to medieval artists depicting the Crucifixion.

In manuscripts and painted works of art that aimed to depict the event, color was frequently exploited to illustrate darkness and to create a dramatic setting. Across media, the celestial bodies of the sun and the moon were incorporated into the skies above the crucifixion, not only to signal darkness at daytime but also to imbue the scenes with a rich cosmological significance.

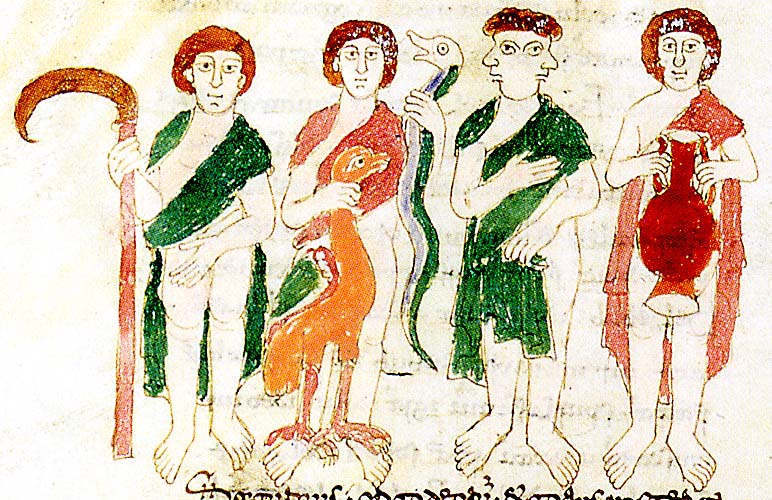

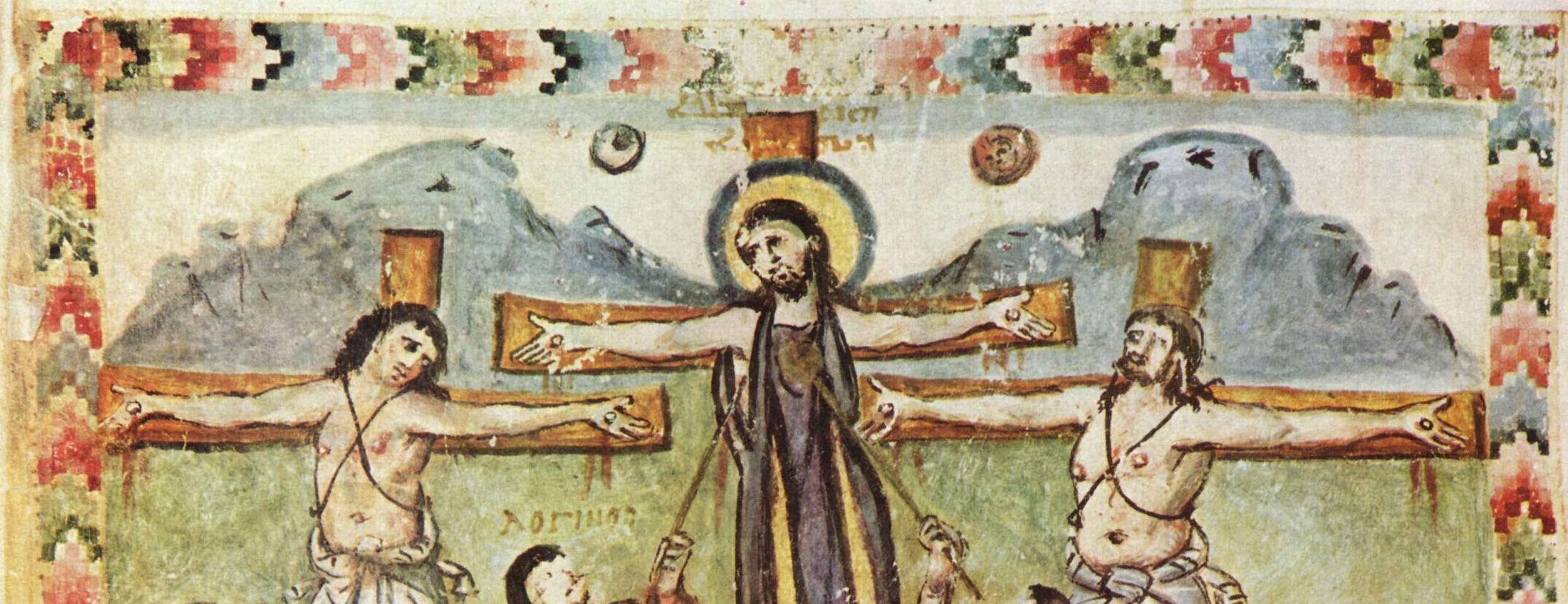

An especially early example appears in the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from the late sixth century. In this manuscript, the Crucifixion includes a partly eclipsed Sun and a Moon with a face against a remarkably light sky; a sliver of shaded pigment at the top suggests darkness (Figure 1). From antiquity, the sun and moon were associated with power. In early medieval crucifixion scenes they represented God’s cosmic anger at the death of Christ.[3] Throughout the Middle Ages, personifications of the Sun and Moon became regular characters at the Crucifixion, positioned as sorrowful figures mourning Christ’s death. The placement of the Sun and Moon respectively at the right and left arms of the cross came to be read typologically as the Old and New Testaments.[4] After about 850, they could also be seen as allegorical representations of Church and Synagogue.[5]

The Ottonian Sacramentary of Henry II sets the Crucifixion scene against a deep purple background, a striking hue used to set a somber mood and suggest darkness (Figure 2). Busts of the personifications Sun and Moon sit on the arms of the cross. The Sun, labeled SOL and sporting a rayed headpiece, and the veiled Moon, labeled LUNA, both turn away from the scene and weep into their draped hands. The strong background color effectively conveys the darkness of this scene emphasized by the dramatic gestures of the Sun and Moon.

Medieval artists sometimes set the same iconographic features within a flattened space of gold or patterned backgrounds. A leaf from the Potocki Psalter, made in Paris in the mid-13th century, sets the Crucifixion against a gold background (Figure 3). Christ is flanked above by the sun and moon and below by the Virgin Mary and the Evangelist John. Within this composition, the three main figures hover between time and space, darkness suggested only by the presence of the partly obscured sun and the crescent moon.

Similarly, in a Crucifixion scene painted around 1400 to 1410 in a Register of Coiners and Minters from Avignon, a richly patterned background of gold scrolls avoids any illusion of a dim sky (Figure 4). The red sun and the moon’s countenance in the upper corners of the miniature are the only clues that the ornamental ground is actually simulated “darkness.” In both miniatures, decorative and luminous backgrounds highlight the central features of the scene so that the Crucifixion image becomes a place of mediation, the background “darkness” metaphorically positioned between an earthly space and a shift in the cosmos at the moment of Christ’s death.

Images of darkness at the Crucifixion can be found in the Index database by any of several possible search strategies. One method is to perform an advanced search using the keyword “Crucifixion” while filtering with the subject “Sun and Moon.” This search returns over 380 results. Executing the search again with the subject “Personification: Sun and Moon” returns around 220 examples in a variety of media, including ivory plaques, glyptics, and frescoes. “Personification: Sun and Moon” is the subject used by the Index for records concerning works on which both celestial bodies have facial features. Using words like “stars” or “starry,” background elements that can also suggest a dark sky may be recorded in the Index’s descriptions of such works.

With the advent of the Index of Medieval Art’s new database, thumbnail images are now visible with search results, allowing the researcher to review works of art at a glance. Thus, a researcher looking into images of the Crucifixion will be able to notice the gradual change in the later medieval period in the West, when images of the Crucifixion began to represent the three-hour darkness as a true night sky. In a Book of Hours made in Paris about 1490, a soft pattern of gold stars with the sun and moon dot a dark blue sky to create the illusion of evening (Figure 5). Other Crucifixion scenes that a researcher may notice while thumbnail browsing show cloudy, dark, and emotive skies that convey darkness without the sun or moon. These atmospheric scenes offer a remarkable and naturalistic, if not peaceful, departure from the earlier ones with their grief-stricken personifications of the Sun and Moon.

The starry night sky casts a familiar source of light over a recognizable scene, and these astronomical bodies inspired fascination in medieval minds still forming theories about what those bodies might actually be. Nevertheless, the symbols of the Sun and Moon, while signaling darkness and the passage of time, also imparted emotional weight, persisting in iconography not only to adhere to scriptural tradition, but also to emphasize the significance of Christ’s death.

Further Reading

Hautecoeur, Louis. “Soleil et la lune dans les crucifixions.” Revue archéologique, ser. 5, XIV (1921): 13-32

Schiller, Gertrude. “The Crucifixion.” In vol. 2 of Iconography of Christian Art, 88–164. London: Lund Humphries, 1972.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Sun, the Moon, and an Eclipse: Observations on The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, by Hendrick Ter Brugghen.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 42 (2007): 121–24.

[1] The Gospels report three other supernatural events that occurred during the Crucifixion: the temple veil was split in two; various earthquakes shook the land; and the souls of the dead rose from their graves. See related subjects in the Index of Medieval Art: Christ: Crucifixion, Earthquake; Christ: Crucifixion, Resurrection of Dead, and Veil of Temple: rending.

[2] Bible Translation. “David Robert Palmer trans., The Gospel of Luke: Part of The Holy Bible.” Accessed 30 March 2018. Bibletranslation.ws/trans/lukewgrk.pdf. See especially p. 116, n. 307.

[3] Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1972), 2:94.

[4] This interpretation was promoted by St. Augustine (354–430 CE). Schiller, 109.

[5] Schiller, 110.