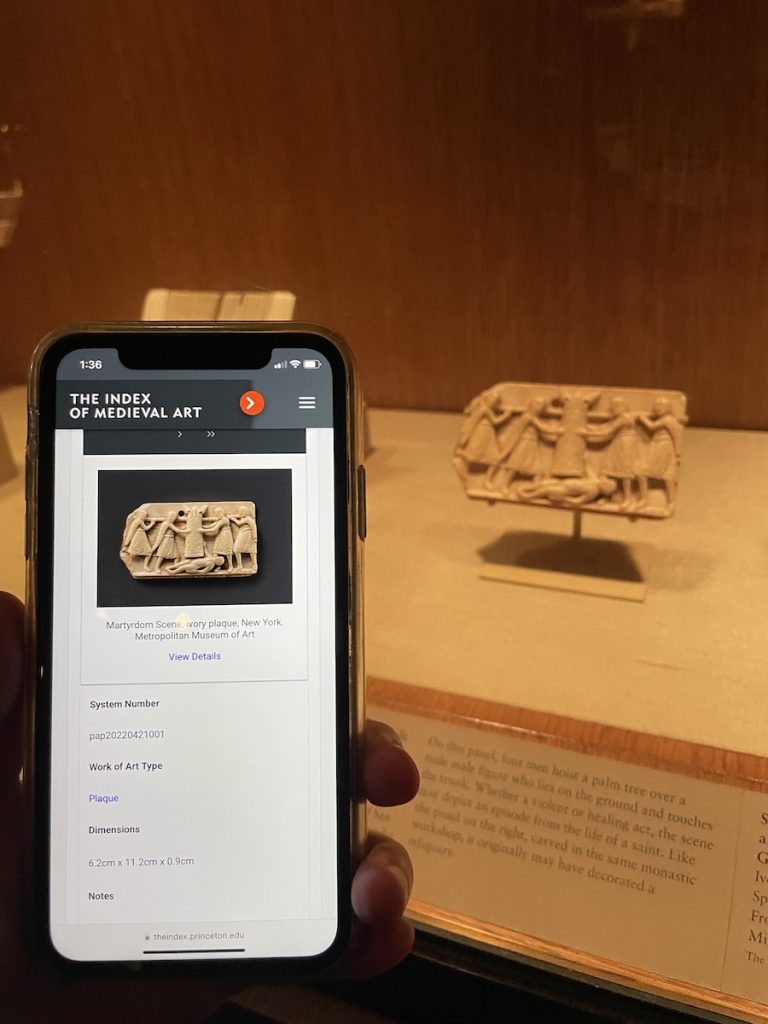

This summer the Index of Medieval Art achieved a milestone in our cataloging mission: the completion of all ivory objects in our print photo archive. In all, more than three thousand objects from the Index’s card catalog have been added to the Index database, significantly enhancing the online collection and establishing the Index as a more vital resource for the study of medieval ivories. The new records include chess pieces, croziers, caskets, combs, retables, diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, knife handles, mirror cases, oliphants, pyxides, statuettes, and much more! Many of the works of art date to the Gothic period, but late antique, early medieval, Romanesque, Carolingian, Siculo-Arabic, and Byzantine works are also well represented. The materials and techniques categorized as “ivory” were also surprisingly diverse, including carvings in walrus tusk, also known as morse, as well as in horn, bone, antler, and even a ceremonial staff made from narwhal tusk.1

The ivory cataloging project was begun shortly after staff returned to in-person work during the later stages of the pandemic. Index research staff worked from inventories of the photo files made by former student assistant Michele Mesi in 2019.2 Many of the photo files dated from the 1930s to 1950s, and they usually provided a subject and photograph with a bibliographic reference, though sometimes they included much less! Working from the clues left by earlier generations of Indexers, the current crew shared key publications and relied when possible on databases, such as the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project, to work through the records alphabetically by location and collection.3

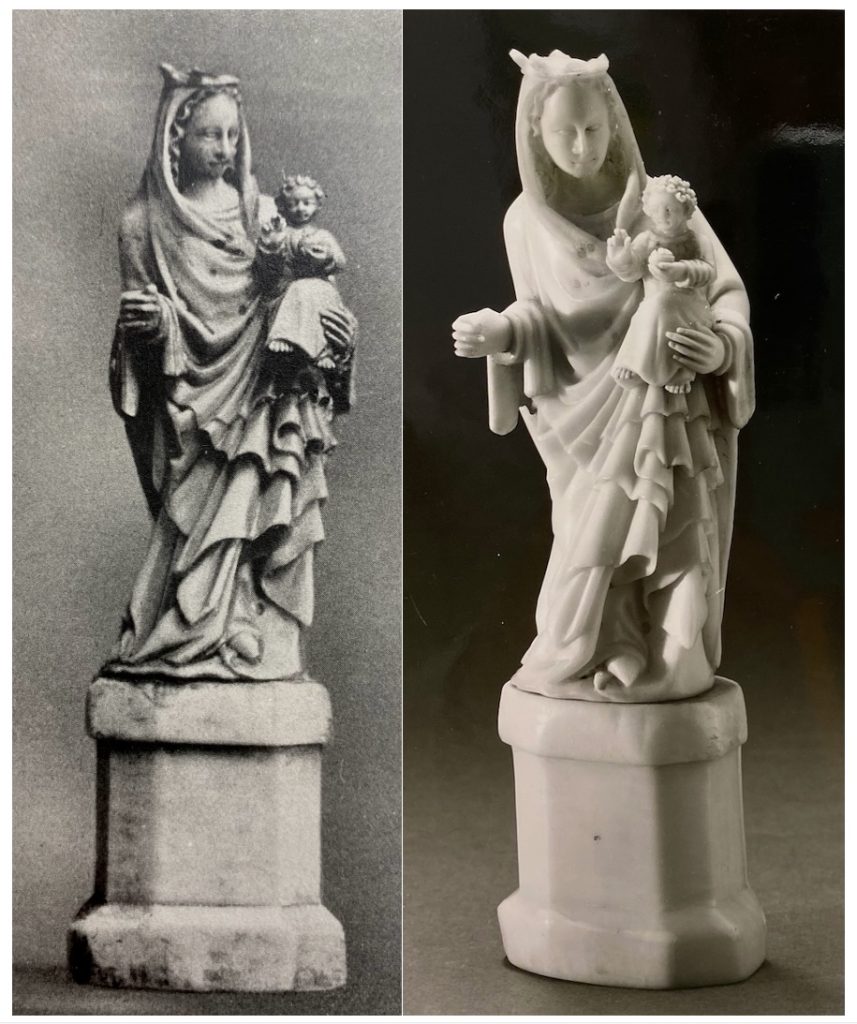

Sometimes we found research clues in unorthodox sources. While researching an early fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Fiore, Art History Specialist Jessica Savage found images shared by the Associazione di Festeggiamenti di Lugnano, Rieti on Facebook. According to the association’s website, the statue is mounted on a gilded decorative support and processed through the streets of Lugnano during the “Festa della Madonna del Fiore” every first Sunday of September.4 It was fascinating to see the medieval relic in celebratory use to this day, and it is just as easy to imagine the lives of these various objects as they were gifted, traded, used, venerated, and now discoverable online with the Index database–many digitized for the first time.

Many of the objects and fragments on which we worked had been dispersed either before or after their records were created, and some items or even whole collections had changed hands. Sometimes this provoked unexpected collaborations: in one case, Art History Specialist Maria Alessia Rossi cataloged the right wing of a diptych in the Musée de Cluny depicting the Coronation and Dormition of the Virgin, and then, about a year later, Savage found the other wing, with the adjoining scenes of the Last Judgment and Adoration of the Magi, separately cataloged in the file of the Paris Cabinet des Médailles. The diptych wings are now digitally reunited as Index System number mar20230306003.

Reflecting on the ivories project, Index Director Pamela Patton said, “One of the most exciting things about cataloging the ivory backfiles was the chance to bring elements of a single object that had been dispersed over time into a single work of art record, as for the Casket of Saint Emilianus (San Millán), a reliquary made in the eleventh century but damaged when the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla was sacked in 1089.” Some of the ivory plaques remain in the monastery, but others were dispersed to at least seven different museums in Europe and the United States. Patton recalled, “Bringing together images and metadata for all these works, including one plaque that was lost in World War II but preserved in a German photograph, was a very satisfying endeavor.”

Byzantine rosette caskets were another category that some researchers may find intriguing. Art History Specialist Henry D. Schilb created a record for the Hermitage Museum’s inv. no. Ѡ17, now Index System number hds20250128001, one of a group of similar caskets cataloged by the Index over the years, with examples in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (inventory number Kg 54:219, Index System number 77286) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (inventory number 1924.747, Index System number 77285). Known for the prominent use of rosette ornament, this group of caskets has also attracted the attention of no less eminent a scholar than Princeton alumnus Justin Willson, whose recent article discusses why we find among scenes of Adam and Eve the figure of Plutus holding a moneybag.5

New iconographic subjects encountered during our work on ivories were sometimes added to the Index database during cataloging. For example, the bust portrait of “Ulpia Sirica,” a second or fourth century woman from Rome, was discovered by Rossi in the ivory files. The only known depiction of Ulpia on this opus sectile-style plaque, made of marble, blue and green enamels, glass paste, and painted bone and ivory listels, was buried by a landslide in the late 1900s. Her portrait is last known to have been embedded in a Latin epitaph in the Catacombs of Saint Agnes in Rome; it is preserved in a late nineteenth-century watercolor by Salvatore Merola, kept in the diary of Ubaldo Giordani.6

Additionally, the little-known female saints “Oderade of Quedlinburg,” “Agnes II of Quedlinburg,” and “Pusinna, Saint” inspired new iconographic research by Art History Specialist Catherine Fernandez during her work on the Reliquary of St. Servatius now housed in the Stift Quedlinburg, Domschatz. The rarely depicted religious women, a prioress, abbess, and hermit, respectively, appear in an iconographic grouping, or relic list, with other saints on the bottom enamel panel of the Reliquary of St. Servatius. The ivory reliquary was made in Fulda or Metz around 870 with gem and metalwork additions ca. 1300.

The ivory cataloging project produced a new authority in the Style/Culture category. We added the heading “Forgery” to describe objects that, although executed in a “medieval” style, were actually—and often with deceptive intent—produced by more modern artists.7 The project also required the verification of a great many locations, part of Schilb’s ongoing project to make the location data used by the Index as accurate and precise as possible.

Indexers celebrated the completion of the ivories project with all staff at an in-house celebration that featured appropriately pale but delectable treats (popcorn, burrata, white chocolate-covered almonds, vanilla meringues!) and offered a chance to reminisce about highlights from the project.8 Many more ivory objects remain to be cataloged by the Index in years to come, but for now we are thrilled to make available online all the objects that have been cataloged by the Index to date. We acknowledge there might still be missing or outdated information on some of these records. Sometimes images could not be tracked down, current locations could not be verified, or works were presumed lost or destroyed. Our cataloging efforts will always be a work in progress, and we remain open to your corrections, suggestions, and questions.

Please reach out to us via email, and be sure to follow us here for all our latest updates. You can also find us on Facebook and Bluesky.

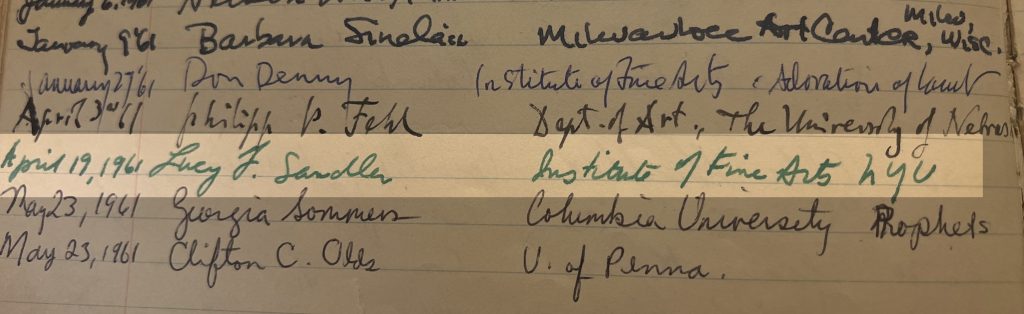

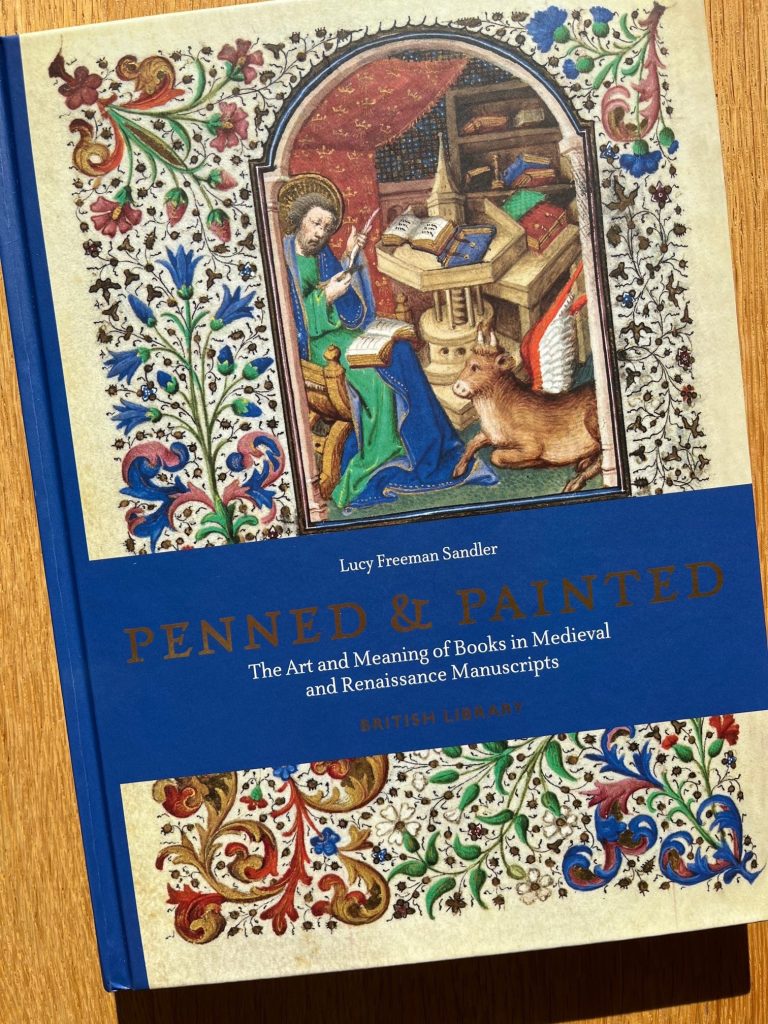

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections and warmly thank Lucy Freeman Sandler, Professor Emerita, Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I began to study painting at Queens College but my first undergraduate art history course focused my interest in a new direction, and, inspired by a charismatic medievalist, Frances Godwin, I decided to study the art of the Middle Ages on the graduate level. On Prof. Godwin’s advice I applied to and was accepted at Columbia University and took courses with Meyer Schapiro, a formative intellectual experience, and then with John Plummer, who was then himself completing a Ph.D. with Schapiro. It was Plummer’s course, called “Gothic Painting,” which was primarily about illuminated manuscripts, in which I “discovered” marginal illustrations, a topic that became the subject of my master’s thesis. For my own Ph.D. I transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (they generously awarded me a scholarship), eventually completing a dissertation on the Psalter of Robert de Lisle (London, British Library, Arundel MS 83).

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

I cannot remember the date of my first visit to the Index, which Index records indicate was 1961, during the time I was working on my dissertation. I have certainly used the Index many times since, and have known all its directors since Rosalie Green, although, to my regret, I did not meet her.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

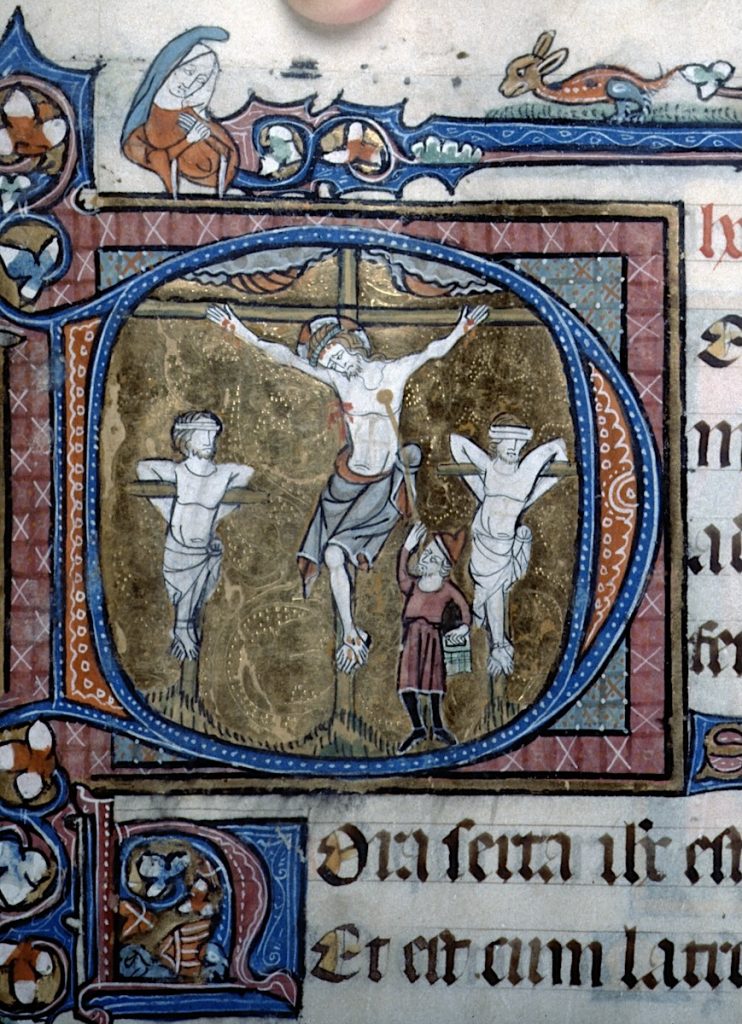

I remember at least one visit, probably sometime between 1961 and 1964, when I was trying to determine the date during the Gothic period at which the crossed feet of the Crucified Christ changed position. I must have looked at hundreds of photos of every late thirteenth and fourteenth century Crucifixion at the Index. I can’t say that I came to any definitive conclusion but I certainly learned a lot about Crucifixion representations. I have found the online version of the Index invaluable, especially in connection with my latest book, Penned & Painted: The Art and Meaning of Books in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2022), for which I did much of the research during Covid.

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I have attended quite a few Index conferences and have spoken at several, including “The Weingarten Office Lectionary and Passionale in New York and St. Petersburg,” in Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century in Honor of Walter Cahn (October 2006); “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Study of the Illuminated Book in England: The Bohun Manuscripts from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” in Gothic Art & Thought in the Middle Ages: A Conference in Honor of Willibald Sauerländer (March 2009); “The Bohun Women and Manuscript Patronage in Fourteenth Century England,” in Medieval Patronage: Patronage, Power and Agency in Medieval Art (October 2012); and “Princeton Garrett MS 35 and Homeless English Gothic Manuscripts,” in Manuscripta Illuminata: Approaches to Understanding Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts (October 2013). All these were subsequently published under the editorship of Colum Hourihane. I also contributed a tribute to John Plummer: “John Plummer: A Reminiscence,” in Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. C. Hourihane (University Park, PA, 2005), 9–11.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As co-editor of the Index-based Studies in Iconography, from 2009–2015, I hoped to serve the mission of the journal, as it has continued to the present, to publish “innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed.”

Thank you, Lucy! As the home for Studies in Iconography we’re committed to publishing innovative work in iconographic studies, and we’re grateful for your invaluable contributions to the Index over so many years.

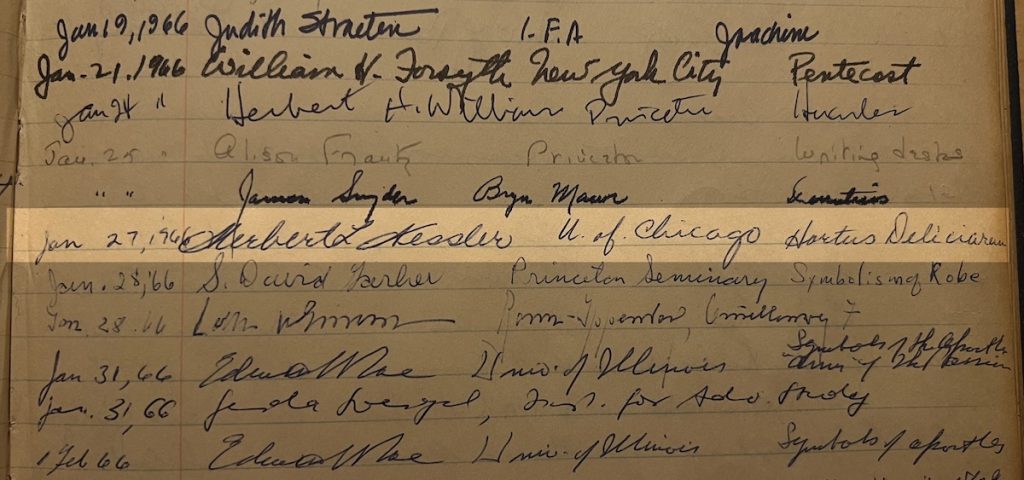

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and we warmly thank Herbert Kessler, Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University and Index friend, for his time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

After studying medieval art as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I completed the MFA and Ph.D. at Princeton. At UC, Margaret Rickert had inspired me to become a medievalist; she was also Rosalie B. Green’s Doktormutter, so Rosalie and I had a special bond from the start. I continued to use the Index at Dumbarton Oaks when I was a Fellow there in 1965–66 and then, again, when I returned to Princeton as a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1969–70.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

RBG1 oriented all new graduate students, so 1961. The Index was then in the Neo-Gothic Cram wing of the original McCormick Hall. Graduate students had keys and used it steadily, especially as a picture resource. The Index staff felt under-appreciated and with good cause: though RBG and Isa Ragusa were distinguished and consistently professional and helpful they knew that the faculty did not respect them as scholars. When I was being recruited to the University of Chicago faculty in 1965, the Dean offered to acquire a copy of the Index for me (because William Heckscher, who had been offered the position earlier, had asked for one), but nothing came of that. As computers were evolving in the 1980s, the Getty Center hired two young persons to recommend ways in which the Index might be digitized. Things did not go well, and I was sent (from Johns Hopkins) to reconcile the Index staff with the Getty interlopers. During the discussions, we all realized how the new technology might allow the Index to be modified in ways better to serve other disciplines, especially e.g. by refining types of musical instruments, botanical and zoological species, or agricultural implements.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I have never used the Index for teaching and, frankly, cannot remember a single eureka moment while using it (except, of course, finding a picture I did not know).

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I gave papers at Iconography at the Crossroads2 and Romanesque Art.3 Both were very important gatherings and publications.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As recently as twenty years ago, one of my own graduate students brushed away an argument with “That’s only iconography,” “Only” was the operative word there. In the wake of the material turn, decolonial turn, global turn, historiographic turn, experiential turn, the ornamental turn, . . . . , searching for texts that identify medieval subjects is no longer sufficient. And with the Patrologia Latina and other compendia online, it is not even fun. Simply to dismiss iconography, however, is ignorant. As I myself have argued at length in a recent essay, “the interweaving of text and image and the sensual pleasure of [medieval art’s] color and rich materials” was the essence of medieval art.4 Iconography is therefore destined to remain a fundamental instrument for studying it.

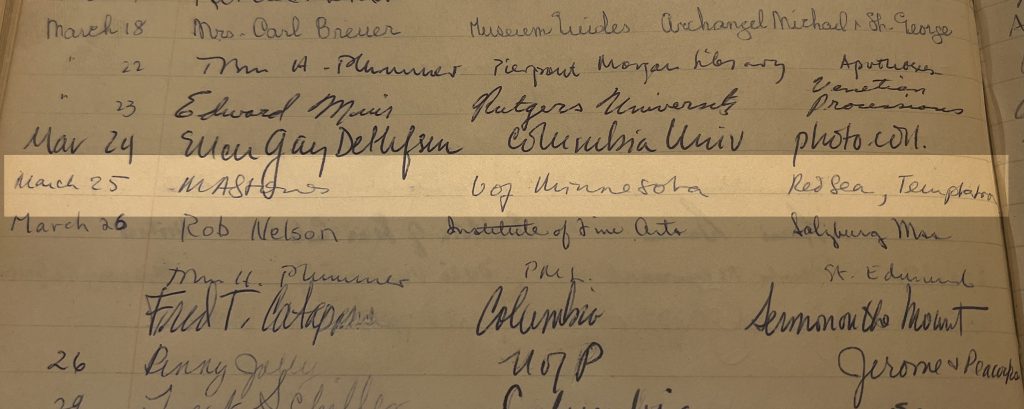

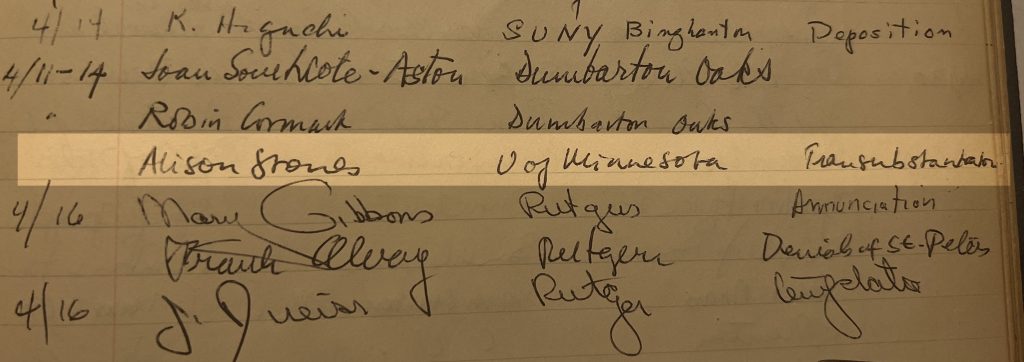

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank Alison Stones, Professor Emerita, University of Pittsburgh, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

In the Fall of 1969, I emerged as a not-quite Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute (that happened a year later in December 1970/January 1971) to begin what would turn out to be a life-long academic career in the United States. My academic background was in French and German literature, followed by a medieval art and architecture specialty at the Courtauld where I worked with the inimitable Christopher Hohler, and with David Ross at Birkbeck, with musicology from Ian Bent at King’s and Heraldry with Nick Norman at the Wallace Collection.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

By 1969 I already had many friends in the US, notably Adelaide Bennett at the Index, Paula Gerson then at Fordham, James Marrow at Binghamton, and Bob Deshman at Toronto, Canada. All of them had worked alongside me in London, so the transition to the US was easy for me and all of them made me feel welcome there. The Index, under Rosalie Green, was among my first stopping places and continued over the years to be a haven for my research on French illuminated manuscripts, from the days of the invaluable old card system up to the new innovations of the 21st century. Adelaide and I would argue back and forth over the limitations and benefits of “Index-Speak” which invited us to hone our descriptive (and analytical) skills, and more recently it was a pleasure to encounter my former student Judith Golden among the ranks of the Index staff. One simply learned so much there!

Under Colum Hourihane came the era of the Index conferences, not-to-be missed sessions of innovative research, captured with regularity in the impressive series of publications produced under his editorship. I was privileged to attend many of these conferences and to participate in Iconography at the Index: Celebrating Eighty Years of the Index of Christian Art (1997),[1] Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus (2004),[2] as well as the festschrift volume Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer (2017).[3] Naturally, these essays all depended heavily on research conducted at the Index, where I must admit that my preference was still the old card system rather than the new, online version. Thankfully, the Index conferences are ongoing, and now available online with a livestream link. From the presentations to the interaction that follows, one learns so much!

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database over the last three decades? Where do you think Index work should go next?

As to future directions for the Index, I wish it could become a repository for the many online medieval databases (my own included) that risk becoming defunct once their creator retires. I appreciate the logistical issues and the problems of different software, but so much creative work is out there, and risks being lost. This in addition to the very valuable repository of information and images that make the Index such an indispensable tool for all medievalists. Long may it continue to flourish and many thanks for all I have learned there!

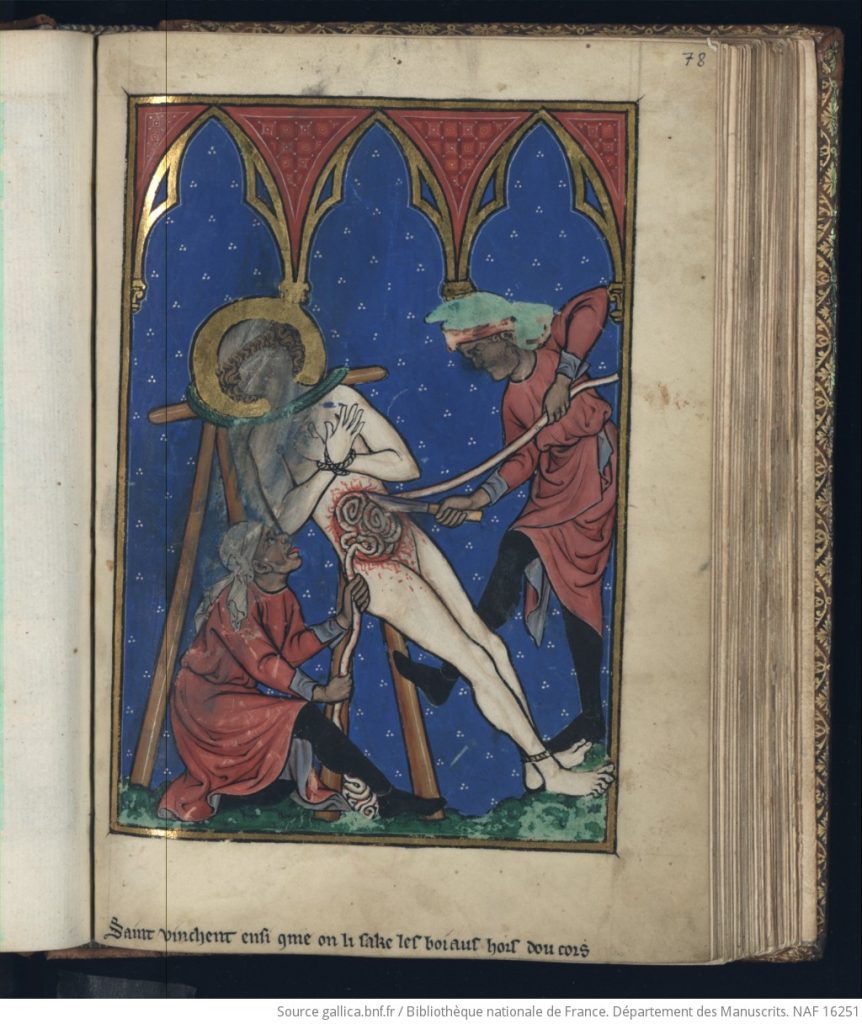

[1] Alison Stones, “Nipples, Entrails, Severed Heads and Skin; Devotional Images for Madame Marie,” in Image and Belief: Studies in Celebration of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 1999), 48–64.

[2] Alison Stones, “Questions of Style and Provenance in the Morgan Picture Bible,” in Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus: A Colloquium in Honor of John Plummer, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 2004), 112–121.

[3] Alison Stones, “Tobit: A Recently Rediscovered Cutting from the Brussels-Rylands Bible,” in Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer, eds. Pamela A. Patton and Judith K. Golden (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2017), 335–353.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to launch a new series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank our interviewees for their time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I’m not a medievalist but my work in Renaissance iconography has always depended on research material from earlier times. I had my first course in art history as a senior in high school, Mary Institute, St. Louis, 1942–1943. I majored art history at Washington University, St. Louis, receiving my M.A. (1949) under H.W. Janson, and did graduate work at the Institute of Fine Art, NYU, with Erwin Panofsky and others. I received my PhD on the basis of three related published articles in 1973.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located then? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

My first visit to the Index was in 1950. For a seminar with Panofsky, I was investigating the sudden appearance of the Infant St. John the Baptist in the Florentine early fifteenth century. The Index was in McCormick Hall. I met Rosalie B. Green and worked with her and Isa Ragusa. I also, by chance, met Professor Morey on that visit. I quickly found that the arrangement of the Index card catalog did not offer simple searching under the Baptist’s name. Learning the biblical structure of the index then helped me broaden the conceptual basis of my project and enriched my results.

In my years of working in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, it was always reassuring to know that the copy of the Index was there for consultation. In the 1980s, when I was a member of the Getty AHIP team, the precedence of the Index was a motivating factor in creating new computer tools for art historical research.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I am told that my article on the iconography of the Infant St. John, published in 1955 in The Art Bulletin remains useful up to the present day.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database? Where do you think Index work should go next?

With the appointment of Pamela Patton, the Index has finally hit its stride. Along with its change of name, broadened constituency, and superb technical improvements, the Index is fast becoming a major research center. It seems to me obvious that these advances indicate that the direction The Index of Medieval Art is going is the right one.

We are very pleased to announce that Kyriaki Giannouli has joined the Index remotely for a three-month, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works on Mount Athos (Greece) into the database!

Kyriaki is a doctoral candidate specializing in Byzantine History at the University of Ioannina and a professional conservator of paintings. Her research focuses on examining the significance of Greek landscapes within the travelogues of Western Holy Land pilgrims from the 12th to the 17th centuries. She is an expert in Byzantine portable icons, frescoes, coins and seals and has hands-on experience in creating specialized conservation reports and working with databases.

At the Index, Kyriaki has started working on enamel and metalwork backfiles and has already made digitally available several objects on Mount Athos, including a fourteenth-century chalice from Vatopedi monastery (Index system number mar20240205001) and an eleventh-century book cover from Lavra monastery (Index system number mar20240212001). Her position requires her to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. This will allow scholars worldwide, who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus, to access these images and their metadata. We are very excited and grateful to have Kyriaki join us in this collaboration!

This position is part of a multi-year project focusing on Mount Athos-related collections at Princeton (https://athoslegacy.project.princeton.edu/) and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

As editorial staff at the Index continue cataloging our physical backfiles, which contain over 200,000 photographs of works of art in sixteen media categories, we are happy to announce that at last, all our print records of gold glass objects have been fully digitized in the Index database! In gold glass, an image in gold leaf is fused between layers of glass. Gold glass was a favored art form in Hellenistic Greece and during the Roman period, often decorating the bases of feasting vessels, such as bowls, cups, and plates, with hidden pictures that would slowly be revealed during the consumption of food and wine. The newly digitized “Gold Glass” backfiles document over 650 objects from about 60 locations. Most examples are identified as vessels, medallions, or plaques (Fig. 1).

The glittering portraits on these glass objects, now mostly fragmentary, are usually bust length and often show whole families. These are classified under the Index subject “Family Group,” while the subject “Married Pair” is used for images depicting a bride and groom, sometimes crowned by Christ. Gold glass objects are frequently associated with marriage celebrations, and several pieces retain the names of the men and women depicted with inscriptions of good wishes. Frequently, this inscription is the Latin drinking toast “PIE ZESES” (“Drink to live,”), either in full or abbreviated, although a fourth-century gold glass fragment from Rome, now in the British Museum, bears the more sentimental words “DVLCIS ANIMA VIVAS” (“Sweet soul, may you live [long]”) around the heads of the newlyweds (Fig. 2).

Several gold glass objects contain other paired figures, especially Peter and Paul the Apostles, as the patron saints of Rome, and Adam and Eve, commonly represented in the Fall of Man scene. Old Testament narratives and figures, such as Moses, Abraham, Daniel, and Jonah were popular, and Christian miracles were also frequently depicted on vessels. The Index database contains just over fifty miracle scenes executed in the gold glass medium, including the Raising of Lazarus, the Miracle of Loaves, and the Wedding at Cana, suggesting that healing themes held some favor among patrons. The objects may also have served a commemorative function.

Some surviving gold glass objects contain Jewish iconographic motifs, including the Temple implements, such as the menorah, shofar, etrog, and Torah Ark. These implements can be found in the Index database by browsing the Subject list, or by searching for “gold glass” as a term and filtering by the Style/Culture “Jewish.” Mythological figures and narratives from the classical world were also favored subjects to depict on gold glass vessels. The Herculean labors, sea-nymphs, and cupids can be identified on some fragments. Other well-represented motifs in the medium include the “Good Shepherd,” which has iconographic connections to the ancient Greek ram-bearing cult figure Kriophoros. There remains much to discover and assess about images in gold glass and their meanings, production, and patronage throughout the late antique, Roman, and Byzantine periods, making the Index an essential study tool. Now, with increased access, more researchers can learn how this rather fragile art form documents fashion, commerce, rituals, and historical names and epigraphs from ancient daily life (Fig. 3).

The Index gold glass backfiles received significant attention by Ryan Gerber, our 2019 summer intern from the Rutgers School of Communication, who is now a Marquand Art Library Collections Specialist. Gerber inventoried the collection and wrote about his impressions in a blog post called “A Face in Gold Glass.” After Henry D. Schilb, Index Art History Specialist in Byzantine Art, finished adding the collection with the help of Gerber’s inventory, he noted that many gold glass objects recorded in major nineteenth century catalogs did not survive into the modern era. Thus, the publications that earlier Index catalogers used in their research may have contained the last known record of an object’s existence. Schilb said, “it was surprising to learn that many of the gold glass objects entered into the Index files have been lost to time, and at least one of them was apparently reduced to dust in the collection where it was last recorded. Not surprisingly, we have also simply lost track of several examples that were originally cataloged by Indexers before the Second World War.” With too little information to go on, the Index cataloger can sometimes upload only a drawing from the catalog and record only a “Last Known Location” for objects presumed lost to history. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this in the database by giving “Unknown” as the current location with a “Last Known Location” to identify the place where an item was last known to exist. This can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are either simply lost or are now in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s true current location, that bit of data can sometimes elude us, so we always welcome intelligence from anyone who might have a good lead!

It is a great achievement when we can complete an entire category in the backfiles with newly researched information, including updated location names, fuller iconographic descriptions, and new or updated terms from Index vocabularies to expand the findability of work of art records. We ought to be clear, however, that we do not claim to have recorded every known example of any medium or type of object. That must remain an ongoing project. Nevertheless, the whole Index team is thrilled to make the gold glass corpus of the original Index card catalog fully available in the database. If you want to see for yourself, you can browse “gold glass” records by Medium more fully here: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/list/ListMediums.action. You can also reach out to us with any inquiry here: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/. Please let us know how the Index can improve the records we have, or find out how the Index can serve your own research needs.

Cheers!

Further Resources

Garrucci, Raffaele. Vetri ornati di figure in oro: Trovati nei cimiteri dei cristiani primitivi di roma. Rome: Tipografia Salviucci, 1858.

Deville, Achille. Histoire de l’art de la verrerie dans l’antiquité. Paris: Morel, 1871.

Vopel, Hermann. Die Altchristlichen Goldgläser: Ein Beitrag zur altchristlichen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg im Breisgau: J. C. B. Mohr, 1899.

Morey, Charles Rufus. The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library: With Additional Catalogues of Other Gold-Glass Collections, ed. Guy Ferrari. Vatican City: Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1959.

Meek, Andrew. New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Howells, Daniel Thomas. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum. London, British Museum Press, 2015.

The Index staff is pleased to announce the relaunch of the Index’s digital image collections, which have recently undergone a massive upgrade. The updated platform hosts ten collections of images generously donated to the Index and made freely accessible to the public through the Index website. These unique documentary resources include more than 50,000 images of medieval art and architecture and reflect the varied interests and travels of their twentieth-century photographers. They represent a range of subjects, techniques, and media, including English medieval embroidery, medieval and Byzantine manuscripts, European choir stall sculpture and stained glass, and Gothic and Romanesque architecture.

Although the images in these collections have not been cataloged with the same level of detail as those in the iconographic database, every effort has been made to assign them basic information regarding location, date, and in many cases, iconographic subjects. The latter can be found in browse lists that include a variety of iconographic topics, including saints and martyrs, animals, zodiac, occupations, and secular and religious scenes, all updated to follow the current subject standards of the main Index database. Browsing these subject lists reveals much about each collection. For instance, the subject list for the “Opus Anglicanum” database—an image collection of medieval English needlework on ecclesiastical and secular textiles—includes numerous saints especially venerated in England, with multiple scenes for Margaret of Antioch, Nicholas of Myra, and Thomas Becket.

Browsing the subject list of another collection, the Elaine C. Block database of misericords, reveals the wide variety of drôleries that decorated the wooden under-seat structures: fantastic creatures, battling animals, and figures playing in sports and games, engaged in occupations, or enacting proverbial lessons. John Plummer’s database of medieval manuscripts includes large numbers of biblical and apocalyptic images, including scenes with Christ, David, and the Virgin Mary, and other popular saints found in late medieval prayer books. The subjects in Plummer’s collection closely resemble those found in Jane Hayward’s collection, perhaps reflecting the shared interests of two scholars were curators at major collections in New York City during the second half of the twentieth century.

The Gabriel Millet collection comprises the study and teaching images of that scholar, an important archaeologist and historian of the early twentieth century who specialized in Byzantine art. Subjects represented here include multiple biblical figures and scenes, but also Byzantine generals and emperors and several text subjects, such as the Chronicle of Manasses and the biblical psalms by number.

The Gertrude and Robert Metcalf Collection of Stained Glass is a documentary treasure for the study of Gothic stained glass. The Metcalfs, who were both stained glass artists and experienced photographers, took more than 11,000 images of stained glass from European monuments, covering sites in Austria, England, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Their images of stained glass windows are a fascinating record of a fragile artistic medium, captured during fragile times. Their travels coincided with the dawn of World War II in Europe over the years 1937 and 1939, and they produced a body of documentary evidence that became critical to postwar restoration efforts. A look at the Metcalf subject list reveals many of the expected themes in medieval iconography, but also significant iconographic cycles for several French bishops, such as Austremonius and Bonitus of Clermont, Germanus of Auxerre, and Martialis of Limoges.

Geographically, the collections cover country and city locations in four continents—Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America—from obscure sites to famous ones, and they include many types of repositories, from in-situ locations to museums, libraries, and private collections. To better accommodate browsing by region, locations in all the collections have been formatted to begin with the country. Each collection is introduced with general information about its history, scope, and image use policies. It has been satisfying to edit and release these collections—now with more consistent information and a more secure digital platform—knowing that they are now more useful to scholars. Your feedback on the collections is welcome via this form.

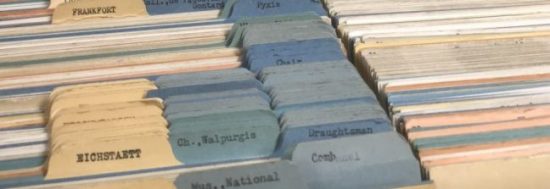

This summer The Index of Medieval Art welcomed two students from the Master of Information program at Rutgers University to inventory the Index’s photographic archive. Comprising nearly two hundred thousand cards in sixteen different medium categories, this historic image collection provides researchers a rich resource of sometimes rare visual references for the study of art produced throughout the Middle Ages. The inventories undertaken by Ryan Gerber and Michele Mesi have illuminated the extent of the archive and helped to assess the image and cataloguing needs for ongoing research and cataloguing at the Index. In this special two-part blog post, we are pleased to present their observations and accounts of their experiences.

It is a testament to the Index’s stimulating power that, despite my lack of an art-historical background, I found myself entranced by the system of cataloguing medieval iconography that the Index pioneered and is still practicing to this day. Its vision of greater accessibility through complete digitization represents another milestone in its long history, and one which will be a gift to scholars of all persuasions and experience levels.

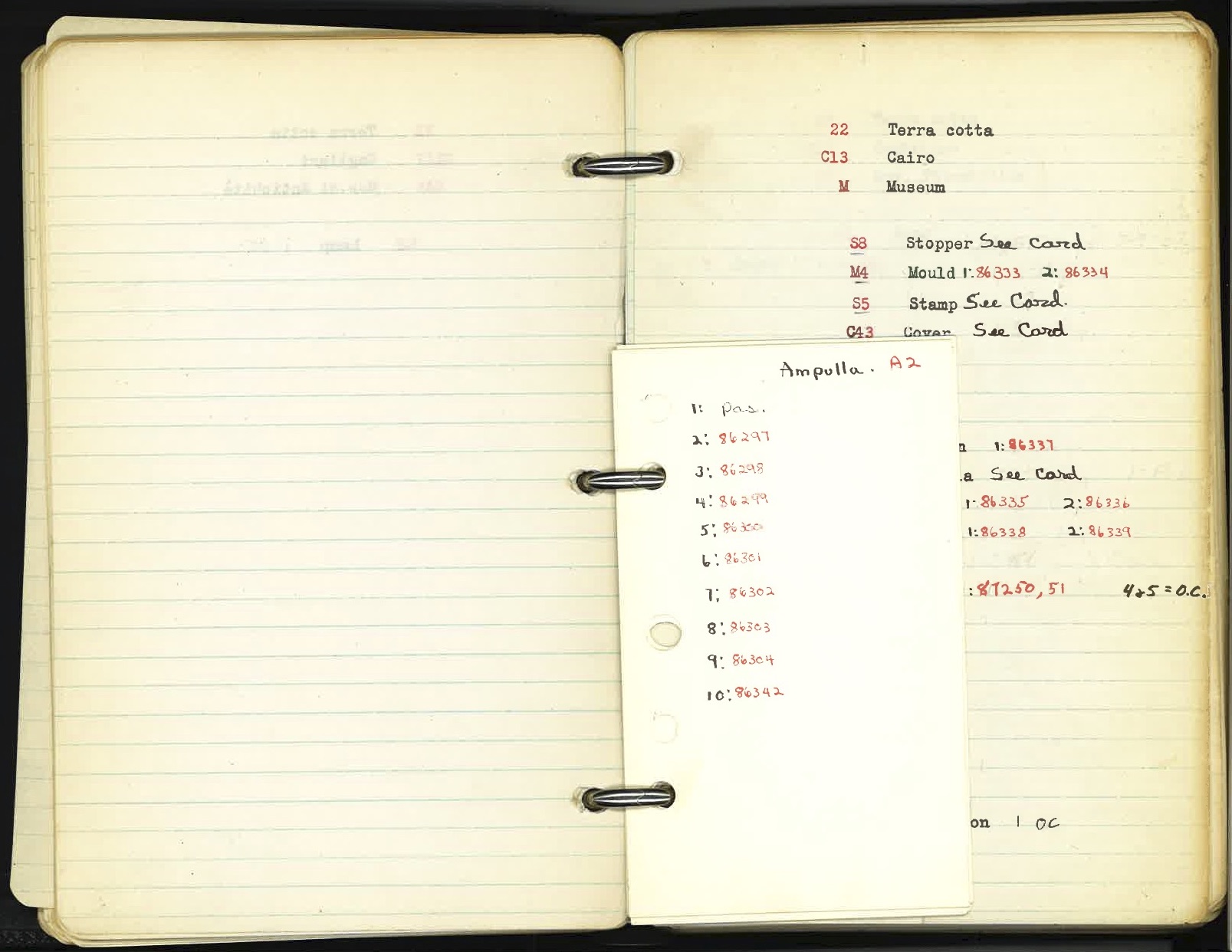

A system largely developed by Index director Helen Woodruff in the 1930s, the photographic archive is organized in the first place by medium, then by location, object type, and the numeric order within that group. Unique codes on the left-hand corner of every index card in the catalogue represent each of these levels of organization. The fruits of this labor are hard to miss after spending any time with the Index and its elegantly interwoven subject index and photographic archive, where one can move seamlessly from subject description to pictorial representations and vice versa.

This work has also left behind a trove of archival resources such as hundreds of rolls of film and the so-called “Black Books” that were used to track the negative numbers. Each of the medium categories I inventoried not only laid the groundwork for further analysis of the collection as a whole, but highlighted the Index’s remarkable century-old ability to generate new curiosities and paths of inquiry.

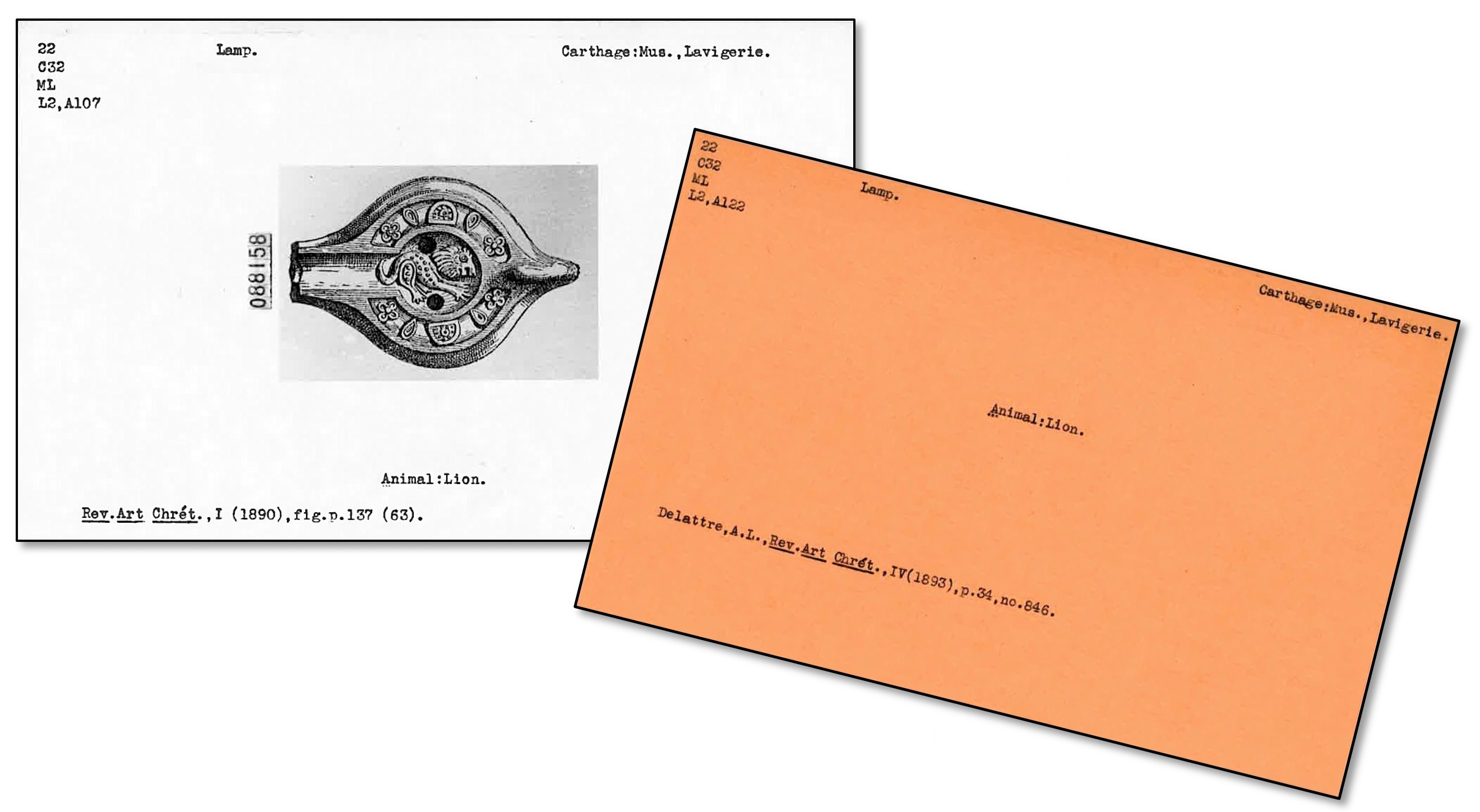

Terracotta, Temporary Cards, Lamps, and Lions

Under the medium “Terra Cotta”—a mixture of clay and water that is formed and baked or fired—the Index records more than twenty-five hundred objects across 196 locations. Of these objects, about sixty-five percent of them are oil lamps. The inventory of these files revealed some of the more common iconographic motifs found on terracotta objects, which include foliate ornament, a variety of land animals and birds, symbols such as crosses, as well as inscriptions and monograms. One terracotta lamp from the Benaki Museum in Athens depicts two of these popular motifs—a lion and a tree—combined on one impressed discus (Fig. 1).

Most photograph cards contain representations of the objects, but they also record the object’s location, the photograph’s negative numbers, subject headings for the image or images on the object, and some bibliographic information. However, there are many temporary “Orange Cards” in the archive that contain only a bibliographic reference and a subject term, and these still await corresponding images. Their inclusion in the original system nonetheless provides important data points about the objects they describe, laying the groundwork for future cataloguers to source the images for these object records. For example, the Index’s photo archive of terracotta objects in the National Museum at Carthage is mostly Orange Cards because the original Index records of these objects derive from a 19th-century publication with very few illustrations. While it would be useful to see images of the “lions” held at the National Museum in Carthage, even in the absence of photographs it may be just as useful to know that, of the 970 terracotta lamps held in that location, nearly four hundred depict animals, and about sixty-five of those include a lion.

A Face in Gold Glass

The “Gold Glass” files record over 650 objects across sixty-three locations dating mostly from late antiquity between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Of these objects, nearly half are vessels of some kind. Gold glass developed as a medium in the ancient Roman and Hellenistic periods and consisted of decorative engravings made in gold leaf, which were then sandwiched between fused layers of glass. The result was lavish decoration, and exemplary pieces in this medium offer strikingly detailed portraits of their subjects, often depicting married pairs, family groups, or religious figures associated with one another, such as Saints Peter and Paul. Historians have noted the rarity of gold glass, as well as its costly, specialized method of production.[1]

Gold glass was a special interest of Index founder Charles Rufus Morey, and his pioneering catalogue of the Vatican Library’s collections features as its first entry an example also catalogued by the Index. It shows the busts of a married couple inscribed above with the name Gregori and a Latin equivalent of “cheers!”: “Gregori bibe [e]t propina tuis,” or “Gregory, drink and drink to thine!” (Fig. 2).[2]

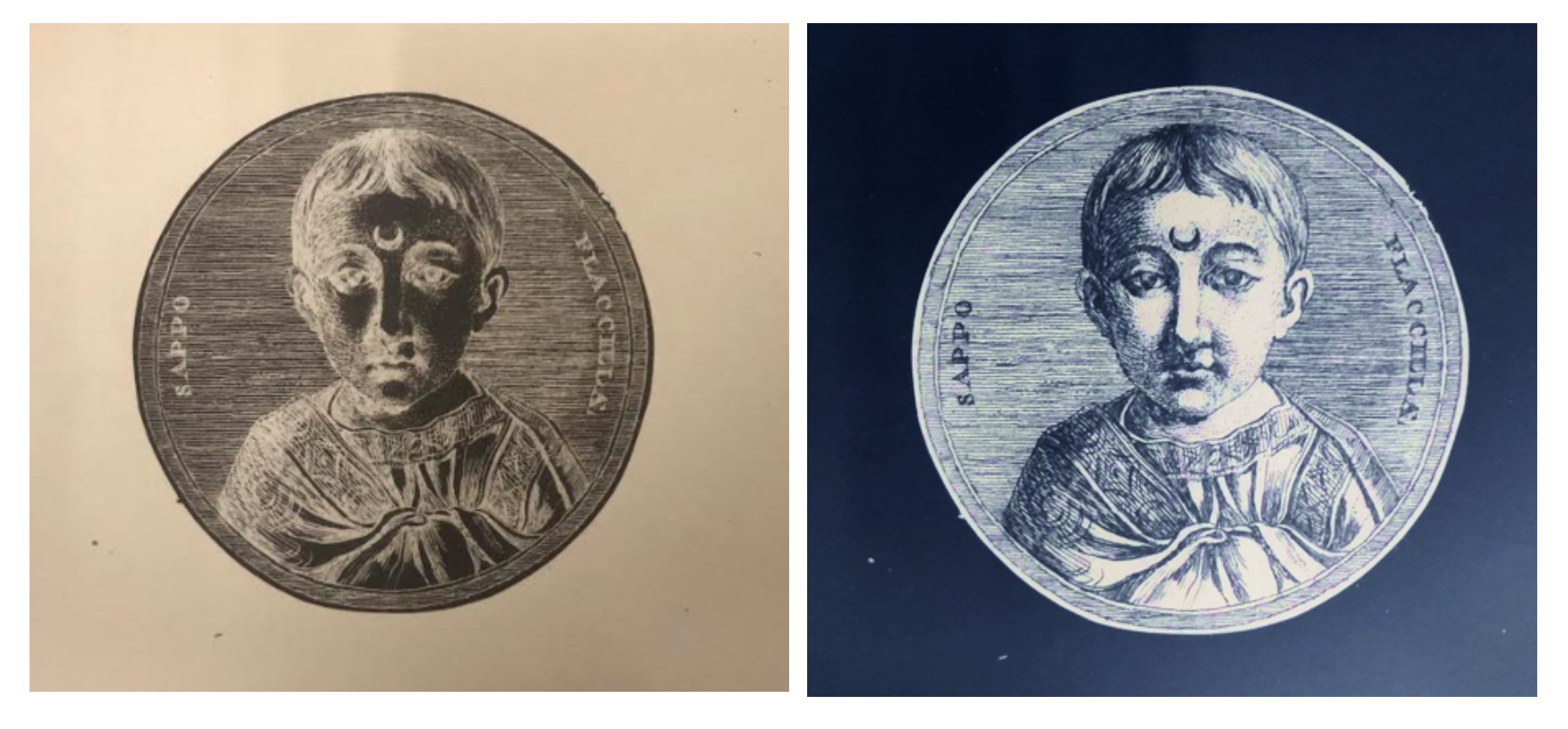

Another interesting discovery in the “Gold Glass” category was a round vessel fragment last recorded in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. It depicts a striking bust of a figure with shorn hair, dressed in a trimmed tunic, and with a distinctive crescent shape on their forehead. The only other information on the photograph card was the source of the image, the antiquities catalogue that Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus published in seven volumes from 1756 to 1767.[3] Caylus’s catalogue was a valuable starting point for identifying this figure, whose iconographic description had not been entered in the Index’s subject files or the database. A little more searching led to a color image in a French catalogue, the Histoire de l’art de la Verrerie dans l’Antiquité (Fig. 3), and to the conclusion that the inscription “SAPPO FLACILLAE”—with the genitive form of the empress’s name—referred to a branded enslaved person who had been freed by the Roman Empress Aelia Flacilla (356–386). We also used the photo-editing web application Pixlr to create a positive image of “Sappo” so that the image from the Index archive can now be seen as it appeared in the catalogue of the comte de Caylus (Fig. 4).

Impressions in Wax

Comprising a little over one thousand objects in 105 locations, the “Wax” medium files are overwhelmingly made up of stamps from Europe dating largely to the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the archive groups these objects into the single object category “Stamp,” the Index database divides them into two Work of Art Types, “Seal Matrix” (that is, the tool used to make the impression) and “Seal Impression” (that is, an impression made by a matrix).[4] Viewing about a thousand examples of Gothic seals intended for both religious and secular officialdom brought into literal relief the development of the production of seal dies from simple figural representations to complex ecclesiastical chapters in miniature, such as the Stamp of Ely Priory, dated to about 1240–1260 (Fig. 5). Other favored subjects in wax seals include heraldry, nobles, and popular saints and bishops, like Thomas Becket. The wealth of iconographic information in the “Wax” files—indeed throughout the archive—emphasizes that the Index is not a closed system, and has at every turn great potential for leading one into new areas of inquiry.

Ryan Gerber is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. He holds an MA in English from The College of New Jersey with a concentration in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. His interests include digital preservation and retrieval, the digital humanities, and information behavior.

See Part 2 written by Michele Mesi.

[1] Giulia Cesarin, “Gold-Glasses: From their Origin to Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean,” in Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–45.

[2] Morey noted of the inscription that “the E of ‘bibe’ or of ‘et’ [was] omitted by mistake.” Charles Rufus Morey, The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1959), 1. Translation after Georg Daltrop in Leonard von Matt, Georg Daltrop, and Adriano Prandi, Art Treasures of the Vatican Library (New York: Abrams, [1970]), 168.

[3] Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1756–57), 193–205, pl. 53.2, https://archive.org/details/recueildantiquit03cayl/page/n10.

[4] See the Index database Work of Art Type browse list to access these Work of Art References.

Precious Gems Containing a Wealth of Iconography

“Glyptic” is among the smaller medium categories in the Index archive, filling only one drawer with a little more than eleven hundred cards that record only about nine hundred objects. The term “glyptics” refers the art of carving gems or seals—whether in intaglio or in relief—typically in gems or precious stones such as jasper, agate, carnelian, and amethyst.[1] This form of art is one of the oldest—known since the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Assyrian civilizations—but it was not until the Hellenistic period that relief cameos, seals, and more intricate glyptic objects began to appear.[2]

Glyptics, which were often worn as jewelry or incorporated into ecclesiastical objects, are recorded in the Index primarily as gems, amulets, plaques, rings, and stamps, and the largest category, cameos, which makes up nearly a third of the glyptic objects in the Index files. A significant portion of the subjects on these carved gems include animals and plant life, like doves, dolphins, fish, palm trees, and fantastic creatures. There are other symbols as well, such as the anchor, which appears on over forty examples. A significant number of glyptics incorporate classical and mythological figures, such as Orpheus, Diana, Jupiter, and Hecate. Nearly twenty cards for gem objects record the Gnostic figure Abrasax (Fig. 1). Glyptics such as these were powerful talismans for their owners.

The traditional use of spiritual amulets was also adopted by Christians using Christian symbols and themes.[3] Christian iconography on glyptics include the triumphant Archangel Michael or Saint George, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and the Good Shepherd. One cameo of opaque black glass made in the 13th century depicts Saint Theodore transfixing the dragon and well represents the preference for saintly imagery on later cameos (Fig. 2).[4] The inventory also revealed that there were nearly thirty examples of incised depictions of monograms on glyptics with a third of them being the Chi-Rho, a symbol for Christ consisting of the first two letters of the word “Christos” (Christ) in Greek.

The major collections represented in this medium include the Staatliche Museen in Berlin (over eighty objects) and the British Museum in London (nearly 125 objects. However, a large number of glyptics (over 140 objects) are recorded as “Location Unknown,” these items having been entered into the Index from major publications that did not provide the precise location at the time of publication.

Radiant Ivories for Both Secular and Religious Narratives

With nearly forty-seven hundred cards covering a little over thirty-one hundred objects, Ivory represented a more extensive category in this inventory project. The types of ivory objects recorded by the Index range from plaques, chess pieces, croziers, and triptychs to the more unusual oliphant (or hunter’s horn) to the handles of various utensils, and even a saddle. Some of the major collections represented in this medium are the Musée du Louvre and the Musée de Cluny in Paris, and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Ivory objects were expertly carved in minute detail, usually from the tusks of elephants. In the Index database, ivory acts as a “parent medium,” an umbrella covering such materials as bone, walrus tusks, and antlers.[5]

Various motifs of courtly love were often depicted on ivory caskets, plaques, mirror cases, combs, and other fine domestic objects.[6] A preference for secular subjects on ivories emerged in the twelfth century when an influx of secular imagery was brought to Europe from the Middle East after the Crusades, as well as through a rise in vernacular literature, legends, and romances.[7] Entertaining stories such as the tale of the Virgin and the Unicorn provided plenty of thematic material to adorn precious ivory objects. They often offered a double meaning or moral lesson, as in the story of Tristan and Isolde depicted on an early 14th-century ivory casket now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which warns against temptations of lust (Fig. 3).[8]

Despite their popularity, secular ivories are fewer in number than devotional works of art in ivory. Roughly a quarter of the ivory objects recorded in the Index are representations of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. This figure rises to more three quarters when we add individual figures of Christ or the Virgin Mary. One type seen rather frequently is that of the Virgin nursing the infant Christ—known in Latin as the Virgo Lactans—which the Index categorizes among the many “types” of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. In the database, the subject heading Virgin Mary and Christ Child, Suckling Type is attached to over 290 Work of Art records. More than forty of these are ivory. This Virgo Lactans iconographic type is exemplified by a 14th-century ivory statuette in the Yale University Art Gallery, which displays an intimate and lifelike relationship between mother and child (Fig. 4). Thus, the devotional message is made personal.

The Project Continues …

Encompassing eight drawers of roughly one thousand cards each, “Painting” proved to be an abundant medium, but “Illuminated Manuscript” is by far the largest medium category in the Index, filling fifty-six of the photograph drawers. Medieval art objects encountered in these two categories range from painted icons and altarpieces to a wide variety of liturgical manuscripts and other illuminated books numbering perhaps in the thousands. The inventory of these and other remaining categories—including those comprising in situ works of monumental art, such as “Mosaic” and “Fresco”—will continue after this summer.

As a “living archive” that covers more than a millennium of artistic creation, the Index of Medieval Art has always been improved and expanded by the interactions of the cataloguers who create it with the with researchers who use it. Creating these inventories has been an illuminating way to participate in that process and to learn more about the contents of the Index card catalogue being prepared for entry into the online database. This project was challenging at times, due to the sheer breadth of the paper files, but it has been an invaluable undertaking for the ongoing process of research and digitization, and will improve accessibility to the records contained in this century-old archive of medieval art.

Michele Mesi is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. From Rutgers University, she also holds a Bachelor’s degree in English with studies in Art History and in Digital Communication, Information, and Media. Her interests include art conservation, archival processing, and working with rare books and manuscripts.

See Part 1 written by Ryan Gerber.

[1] The Index of Medieval Art follows the standards for material description established by the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). See the Art & Architecture Thesaurus® Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/.

[2] O. Neverov and A. Durandin, Antique Intaglios in the Hermitage Collection (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1976), 7.

[3] Neverov and Durandin, Antique Intaglios, 8.

[4] The Index records the iconography in question as Theodore Tyro or Theodore the General, Slaying Dragon.

[5] See the glossary entry on the Index database Medium browse list for “ivory.”

[6] J. Lowden and J. Cherry, Medieval Ivories and Works of Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Art Gallery of Ontario, 2008), 122.

[7] R. H. Randall, “Popular Romances Carved in Ivory,” in Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1997), 63.

[8] Randall, “Popular Romances,” 67–68.