NB: This satirical post was shared in honor of April Fool’s Day, 1 April, 2021

We might consider baseball as American as apple pie. Popular legend ascribes its invention to Abner Doubleday in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, while historians of the sport point out that a similar game was played in North America as early as the late eighteenth century. Some, however, have hypothesized that the game had earlier roots in two early modern English games, rounders and cricket.

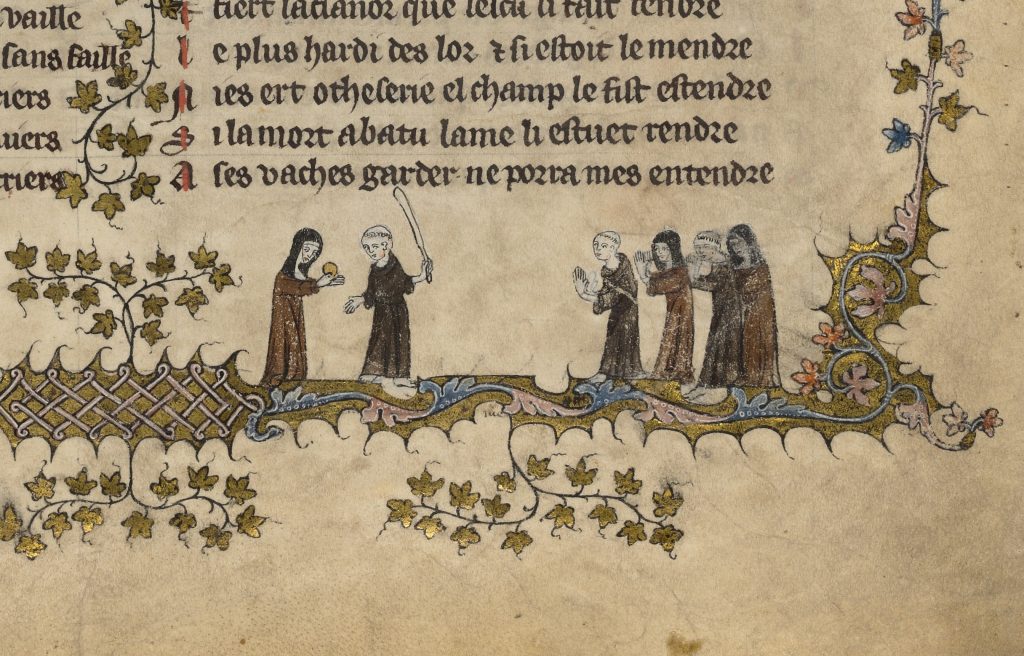

Yet there is evidence to suggest that baseball has far deeper historical roots, reaching back to the Middle Ages. The marginal decoration of a fourteenth-century French manuscript now in Oxford’s Bodleian Library (MS. 264) includes what may be the earliest conclusive illustrations of the game, played here by a group of nuns and monks. The nun at left has caught the ball just after the monk at bat has swung and missed. The monk turns to argue the count as two monks and two nuns in the infield raise their hands, ready to field, in a classic example of what Otto Pächt has called “simultaneous narrative.” The absence of outfielders in the scene was surely the result of artistic economy, given the limited space afforded by the gilded floral and foliate border, a decorative form that perhaps inspired the much later planting of ivy on the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, where players still contend with limited space.

The representation of the game’s players as cloistered religious figures offers a note of accuracy, as French nuns are in fact the earliest recorded players of the game that they called le base-bal. As early as the twelfth century, the nuns of the Abbey of Fontevraud in particular had established a reputation for their high on-base percentage and daring in run-downs; a certain Wilgefortis is lauded in conventual records for her lusty swing and reliability in the clutch. Barnstorming throughout the Loire valley, the Fontevraud nuns found the women of other convents eager to meet them between the lines, although the same could not be said of the monks and canons they challenged, most of whom refused to play, claiming the women “couldn’t throw.” The mixed-gender matchup depicted in the fourteenth-century Bodleian manuscript reflects a later era, when the dominance of the Fontevraud lineup had faded into distant memory and monks became more willing to test their skills against their slugging sorores.

Conventual baseball faded in Europe in the sixteenth century as reformers like Martin Luther turned popular opinion against the “devil’s game,” describing it as a gateway to luxury and vice and also complaining that the action was “too slow.” Today, it is only pictorial traces like that in Bodleian 264 that preserve the vibrant medieval traditions that gave us “America’s pastime.”