As our regular readers know, the Index of Medieval Art recently launched a redesigned database. A challenging part of preparing for this event (codenamed Project Phoenix) was revisiting, reevaluating, and often revising how the Index has traditionally presented certain types of information. A century of accumulated data can reveal some unexpected things. Since the Index was founded in 1917, the history of the world has been…oh, let’s just call it “eventful.” Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the process of updating our outdated records as we upgrade the Index database has been a sobering reminder of all that has changed in the world, all that we have learned and achieved, and all that we have lost over the last one hundred years.

One set of data that made the need to revise our records very clear to us was the place names that we use. Obviously, names change, but we can point to a variety of reasons for the outdated information in the Index database. Some names in English are translations from the language of the place in question. In English usage, Wien remains Vienna, and Firenze remains Florence, but Lyon has superseded Lyons. Sometimes it’s a question of both language and script. What rules of translation and transliteration should we prefer? Depending on who is speaking or writing, a single place can be known by many names. For example, the Armenian place name Հռոմկլա can be transliterated as Hromkla, Hṛomkla, Hṛomklay, or Hrongla, but it can also be Rum Kalesi, Rūm ḳal‘esi, Rumkale, Qal‘ah Rumita, Qal‘at al-Rum, Qal‘at al-Muslimin, or Kela zêrîn. Can a single rule be applied consistently and make sense to users of the Index?

No matter the topic under discussion among the research staff at the Index, the answer to that last question turns out to be “no” frustratingly often. Language, like the rest of the world, is just too messy. One of our solutions, at least regarding how we handle locations, has been to embrace the messiness so that we simply have to account for complexity. So, when choosing an authority to cite for place names (authorities such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographical Names and the Library of Congress, among others), we quickly decided that we need not cite the same authority in every case.

In addition to the problem of language, there are also outright changes of name that we have to recognize. The city of Byzantium has gone by a few different names in its history (Fig. 1). It’s called Istanbul now, but Istanbul was Constantinople. Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople. Believe it or not, that change became official many years after the Index was founded. It’s also worth mentioning that, although the name of that city should really be spelled “İstanbul” in Modern Turkish (with a dotted capital “İ”), the Index will continue to use the spelling familiar to English readers. Thus, even for something in situ, the database might list different names for an object’s or monument’s location of origin and its current location. Hagia Sophia is in Istanbul, but it was in Constantinople. (Have we given you an earworm yet?) Nevertheless, as we update the Index database, we will cross-reference place names so that, for example, a search for Istanbul (or İstanbul) will always also lead you to Constantinople.

But it’s not only names that change. Borders also sometimes shift. Once upon a time, when the Index was new, the city of Königsberg was in Prussia. After World War I, Königsberg was part of Germany (the Weimar Republic, that is, and then Nazi Germany), and by the end of World War II, much of the city had been destroyed, including museums and medieval monuments. That makes Germany the last known location for those buildings and the objects they contained (Fig. 2). Once the Prussian home of Immanuel Kant, Königsberg is now within the Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. And, oh yes, it’s called Kaliningrad now. Our goal at the Index of Medieval Art is to continue to update our database to account for such changes.

By the way, for those of you as interested in topology as you are in topography, Kaliningrad was—when it was Königsberg—the subject of a famous logic puzzle. The city straddles the Pregel River, and there are two islands in the river, a feature reminiscent of Paris. The islands in Königsberg were connected to the rest of the city, but the bridges were configured in such a way as to give rise to this puzzle: “Can you walk through Königsberg crossing each of the seven bridges only once?” This puzzle has rules, of course: you have to cross each bridge only once, and you must cross each bridge completely (without turning around in the middle), but you may not cheat with a boat or hot air balloon. The puzzle was solved in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler, the great Swiss mathematician and general smarty-pants. When it comes to walking through Königsberg, crossing each of the seven bridges only once, Euler proved that…spoiler alert…it couldn’t be done!

Time does things to maps. Not only do place names change and frontiers shift, but cities rise and fall, roads are rerouted or renamed, and buildings are razed or rebuilt. Sometimes new bridges replace old ones, so that even that famous logic puzzle about the seven bridges of Königsberg has been affected by the last two centuries of human history. Only two of the bridges that Euler knew still exist, and the new configuration of bridges means that the Königsberg puzzle is no longer a puzzle at all in Kaliningrad!

On a related note, have you ever wondered, “When is a map not a map?”

More precisely, the question that arose recently at the Index was this: “When is a map a map, and when is it a representation of a map?” Questions like this one can lead to surprisingly lively discussions at the Index of Medieval Art. This particular question came up while we were discussing how the Index ought to categorize certain subjects. It seems clear that some things are maps, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi. It also seems clear that some images include representations of maps, without actually being maps (Fig. 3).

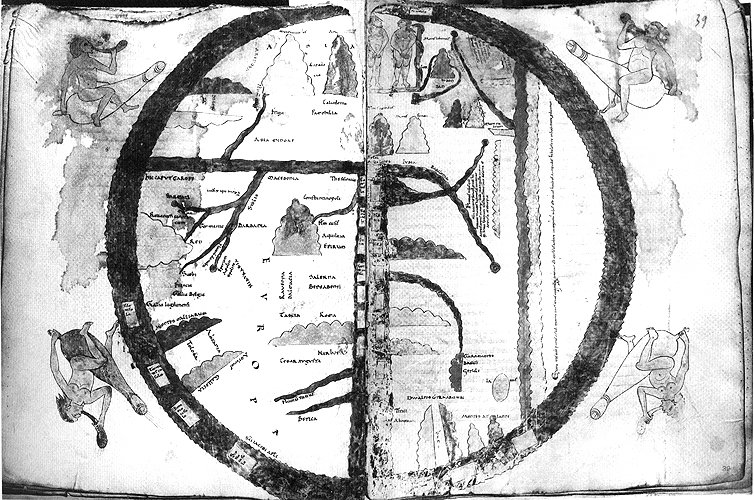

However, some cases may be less clear, like a map in the Turin Beatus (Fig. 4). Is this an illumination that consists of a map, or is it a representation of a map? In other words, when is an object a map, and when is “map” the subject of an image?

What we at the Index sincerely hope is that you, everyone who uses the Index, will join us in addressing such questions. We invite subscribers to try out the Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. We welcome your thoughts, so please tell us about your experience using the database, or share your observations about how we handle the content. Please bear in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them. It will also take us some time to edit the contents of the database so that everything is handled consistently within our revised format. In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers, and it will continue to be available until we are confident that the new version can supersede the old one.

We look forward to hearing from you. Your insights and feedback will continue to be vital to the success of this enterprise, just as they have been through the first 100 years of the Index of Medieval Art.

Henry Schilb