This summer the Index of Medieval Art achieved a milestone in our cataloging mission: the completion of all ivory objects in our print photo archive. In all, more than three thousand objects from the Index’s card catalog have been added to the Index database, significantly enhancing the online collection and establishing the Index as a more vital resource for the study of medieval ivories. The new records include chess pieces, croziers, caskets, combs, retables, diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, knife handles, mirror cases, oliphants, pyxides, statuettes, and much more! Many of the works of art date to the Gothic period, but late antique, early medieval, Romanesque, Carolingian, Siculo-Arabic, and Byzantine works are also well represented. The materials and techniques categorized as “ivory” were also surprisingly diverse, including carvings in walrus tusk, also known as morse, as well as in horn, bone, antler, and even a ceremonial staff made from narwhal tusk.1

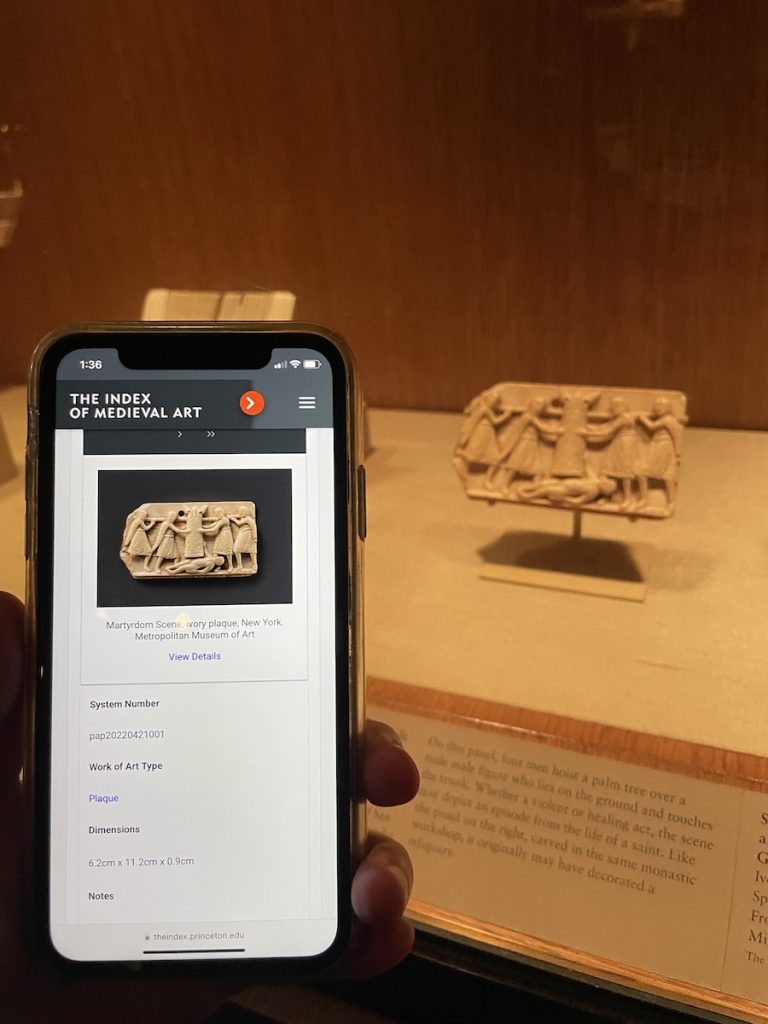

The ivory cataloging project was begun shortly after staff returned to in-person work during the later stages of the pandemic. Index research staff worked from inventories of the photo files made by former student assistant Michele Mesi in 2019.2 Many of the photo files dated from the 1930s to 1950s, and they usually provided a subject and photograph with a bibliographic reference, though sometimes they included much less! Working from the clues left by earlier generations of Indexers, the current crew shared key publications and relied when possible on databases, such as the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project, to work through the records alphabetically by location and collection.3

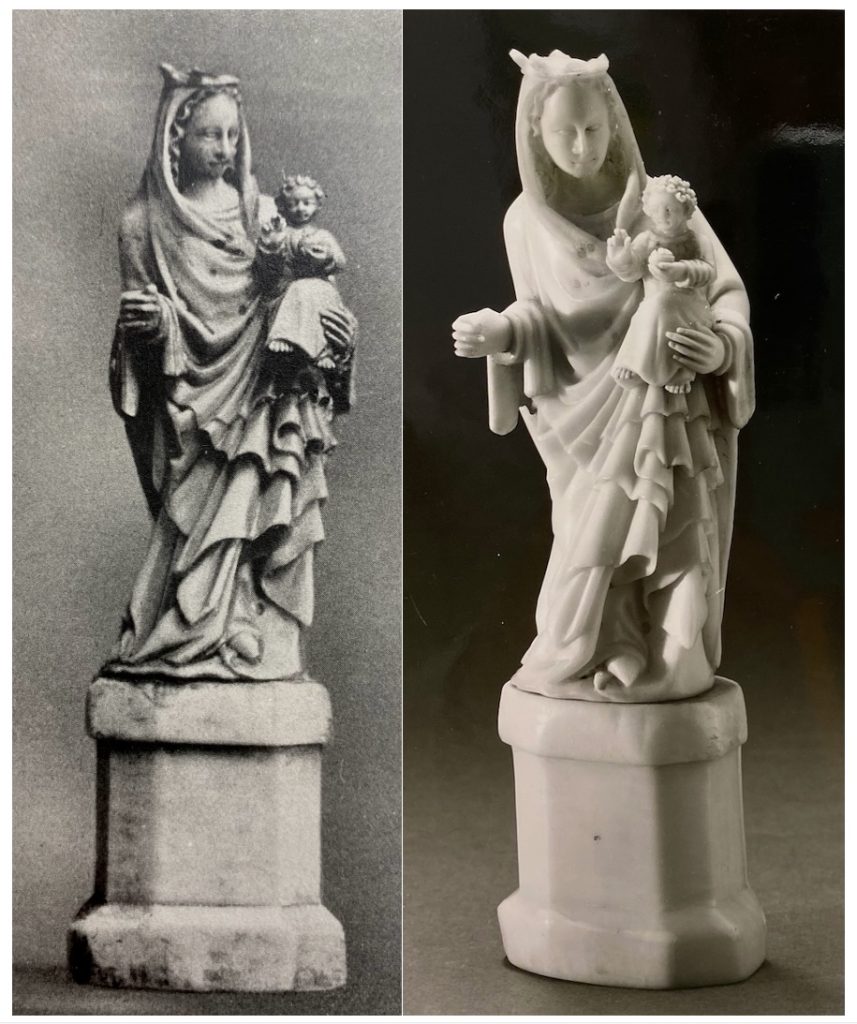

Sometimes we found research clues in unorthodox sources. While researching an early fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Fiore, Art History Specialist Jessica Savage found images shared by the Associazione di Festeggiamenti di Lugnano, Rieti on Facebook. According to the association’s website, the statue is mounted on a gilded decorative support and processed through the streets of Lugnano during the “Festa della Madonna del Fiore” every first Sunday of September.4 It was fascinating to see the medieval relic in celebratory use to this day, and it is just as easy to imagine the lives of these various objects as they were gifted, traded, used, venerated, and now discoverable online with the Index database–many digitized for the first time.

Many of the objects and fragments on which we worked had been dispersed either before or after their records were created, and some items or even whole collections had changed hands. Sometimes this provoked unexpected collaborations: in one case, Art History Specialist Maria Alessia Rossi cataloged the right wing of a diptych in the Musée de Cluny depicting the Coronation and Dormition of the Virgin, and then, about a year later, Savage found the other wing, with the adjoining scenes of the Last Judgment and Adoration of the Magi, separately cataloged in the file of the Paris Cabinet des Médailles. The diptych wings are now digitally reunited as Index System number mar20230306003.

Reflecting on the ivories project, Index Director Pamela Patton said, “One of the most exciting things about cataloging the ivory backfiles was the chance to bring elements of a single object that had been dispersed over time into a single work of art record, as for the Casket of Saint Emilianus (San Millán), a reliquary made in the eleventh century but damaged when the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla was sacked in 1089.” Some of the ivory plaques remain in the monastery, but others were dispersed to at least seven different museums in Europe and the United States. Patton recalled, “Bringing together images and metadata for all these works, including one plaque that was lost in World War II but preserved in a German photograph, was a very satisfying endeavor.”

Byzantine rosette caskets were another category that some researchers may find intriguing. Art History Specialist Henry D. Schilb created a record for the Hermitage Museum’s inv. no. Ѡ17, now Index System number hds20250128001, one of a group of similar caskets cataloged by the Index over the years, with examples in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (inventory number Kg 54:219, Index System number 77286) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (inventory number 1924.747, Index System number 77285). Known for the prominent use of rosette ornament, this group of caskets has also attracted the attention of no less eminent a scholar than Princeton alumnus Justin Willson, whose recent article discusses why we find among scenes of Adam and Eve the figure of Plutus holding a moneybag.5

New iconographic subjects encountered during our work on ivories were sometimes added to the Index database during cataloging. For example, the bust portrait of “Ulpia Sirica,” a second or fourth century woman from Rome, was discovered by Rossi in the ivory files. The only known depiction of Ulpia on this opus sectile-style plaque, made of marble, blue and green enamels, glass paste, and painted bone and ivory listels, was buried by a landslide in the late 1900s. Her portrait is last known to have been embedded in a Latin epitaph in the Catacombs of Saint Agnes in Rome; it is preserved in a late nineteenth-century watercolor by Salvatore Merola, kept in the diary of Ubaldo Giordani.6

Additionally, the little-known female saints “Oderade of Quedlinburg,” “Agnes II of Quedlinburg,” and “Pusinna, Saint” inspired new iconographic research by Art History Specialist Catherine Fernandez during her work on the Reliquary of St. Servatius now housed in the Stift Quedlinburg, Domschatz. The rarely depicted religious women, a prioress, abbess, and hermit, respectively, appear in an iconographic grouping, or relic list, with other saints on the bottom enamel panel of the Reliquary of St. Servatius. The ivory reliquary was made in Fulda or Metz around 870 with gem and metalwork additions ca. 1300.

The ivory cataloging project produced a new authority in the Style/Culture category. We added the heading “Forgery” to describe objects that, although executed in a “medieval” style, were actually—and often with deceptive intent—produced by more modern artists.7 The project also required the verification of a great many locations, part of Schilb’s ongoing project to make the location data used by the Index as accurate and precise as possible.

Indexers celebrated the completion of the ivories project with all staff at an in-house celebration that featured appropriately pale but delectable treats (popcorn, burrata, white chocolate-covered almonds, vanilla meringues!) and offered a chance to reminisce about highlights from the project.8 Many more ivory objects remain to be cataloged by the Index in years to come, but for now we are thrilled to make available online all the objects that have been cataloged by the Index to date. We acknowledge there might still be missing or outdated information on some of these records. Sometimes images could not be tracked down, current locations could not be verified, or works were presumed lost or destroyed. Our cataloging efforts will always be a work in progress, and we remain open to your corrections, suggestions, and questions.

Please reach out to us via email, and be sure to follow us here for all our latest updates. You can also find us on Facebook and Bluesky.