Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

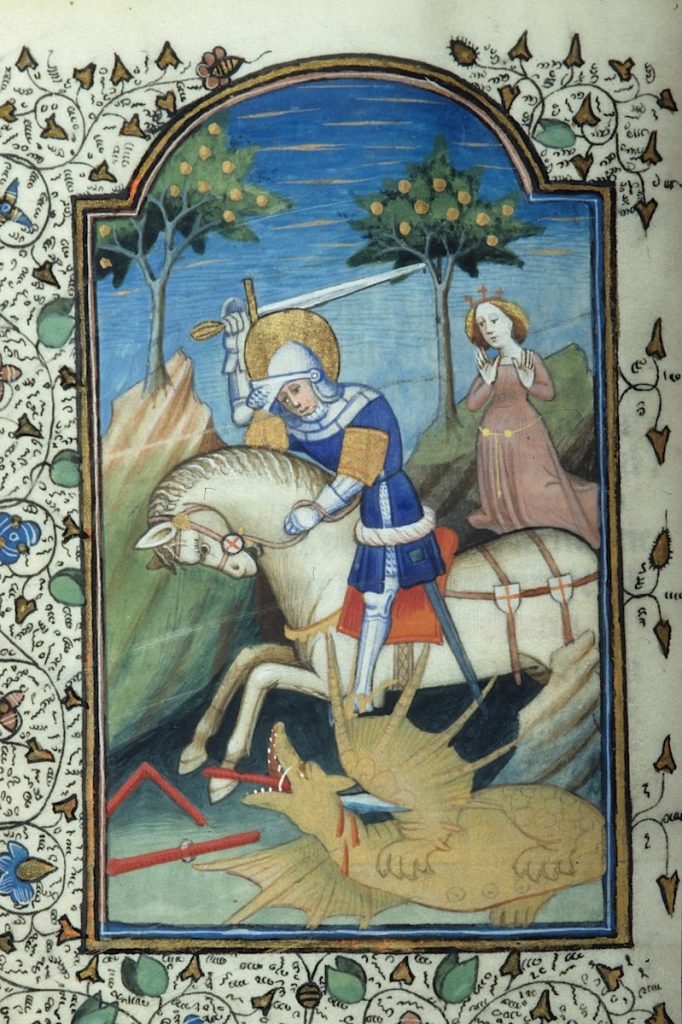

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art: