The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and we warmly thank Herbert Kessler, Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University and Index friend, for his time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

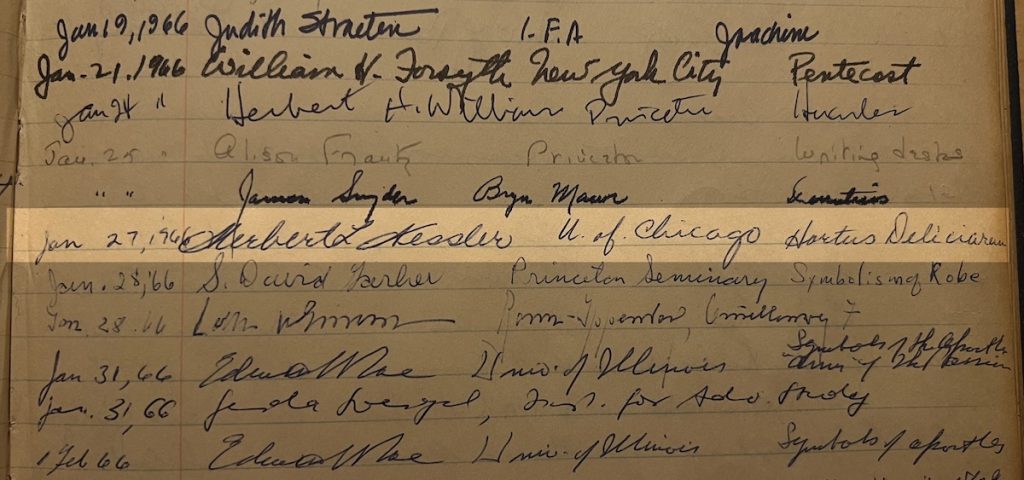

After studying medieval art as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I completed the MFA and Ph.D. at Princeton. At UC, Margaret Rickert had inspired me to become a medievalist; she was also Rosalie B. Green’s Doktormutter, so Rosalie and I had a special bond from the start. I continued to use the Index at Dumbarton Oaks when I was a Fellow there in 1965–66 and then, again, when I returned to Princeton as a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1969–70.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

RBG1 oriented all new graduate students, so 1961. The Index was then in the Neo-Gothic Cram wing of the original McCormick Hall. Graduate students had keys and used it steadily, especially as a picture resource. The Index staff felt under-appreciated and with good cause: though RBG and Isa Ragusa were distinguished and consistently professional and helpful they knew that the faculty did not respect them as scholars. When I was being recruited to the University of Chicago faculty in 1965, the Dean offered to acquire a copy of the Index for me (because William Heckscher, who had been offered the position earlier, had asked for one), but nothing came of that. As computers were evolving in the 1980s, the Getty Center hired two young persons to recommend ways in which the Index might be digitized. Things did not go well, and I was sent (from Johns Hopkins) to reconcile the Index staff with the Getty interlopers. During the discussions, we all realized how the new technology might allow the Index to be modified in ways better to serve other disciplines, especially e.g. by refining types of musical instruments, botanical and zoological species, or agricultural implements.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I have never used the Index for teaching and, frankly, cannot remember a single eureka moment while using it (except, of course, finding a picture I did not know).

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I gave papers at Iconography at the Crossroads2 and Romanesque Art.3 Both were very important gatherings and publications.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As recently as twenty years ago, one of my own graduate students brushed away an argument with “That’s only iconography,” “Only” was the operative word there. In the wake of the material turn, decolonial turn, global turn, historiographic turn, experiential turn, the ornamental turn, . . . . , searching for texts that identify medieval subjects is no longer sufficient. And with the Patrologia Latina and other compendia online, it is not even fun. Simply to dismiss iconography, however, is ignorant. As I myself have argued at length in a recent essay, “the interweaving of text and image and the sensual pleasure of [medieval art’s] color and rich materials” was the essence of medieval art.4 Iconography is therefore destined to remain a fundamental instrument for studying it.