As of April 1, 2021, the Index-hosted journal Studies in Iconography has shifted to an online submission process, beginning with submissions for volume 43 (2022). Prospective authors may submit their manuscripts on our new Scholarworks site and will find further information both there and in the editorial policies and guidelines section of the IMA website. In addition, beginning with vol. 42 the journal’s annual volumes will be published both in print and online through Scholarworks, a shift that is hoped will increase their reach and accessibility.

Studies in Iconography is an annual journal hosted by the Index of Medieval Art and published in partnership with Medieval Institute Publications. Co-edited by Pamela A. Patton and Diliana Angelova, it presents innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed, between the fourth century to the year 1600. Past and current articles have addressed subjects as diverse as Byzantine fresco programs, Carolingian architectural diagrams, Gothic rent books, Jewish ritual images, Islamicate stucco ornament, and early modern portraiture. We especially encourage article submissions that offer interdisciplinary, theoretical, or critical perspectives, and works of both established and emerging scholars are welcome. Reviews of selected books on iconography and art history are included in every volume.

Inquiries about matters outside the online submission process may be directed to Fiona Barrett, fionab@princeton.edu.

For information about pricing, subscriptions, or back issues, please consult https://wmich.edu/medievalpublications/journals/iconography.

The Index of Medieval Art has completed a systemwide update aimed at making the database both more user-friendly and fully compliant with current accessibility standards. Launched April 1, the update includes the following improvements:

We encourage researchers to explore the updated site, making use of the new Help pages linked on the Welcome page. As always, we welcome your research inquiries and feedback.

NB: This satirical post was shared in honor of April Fool’s Day, 1 April, 2021

We might consider baseball as American as apple pie. Popular legend ascribes its invention to Abner Doubleday in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, while historians of the sport point out that a similar game was played in North America as early as the late eighteenth century. Some, however, have hypothesized that the game had earlier roots in two early modern English games, rounders and cricket.

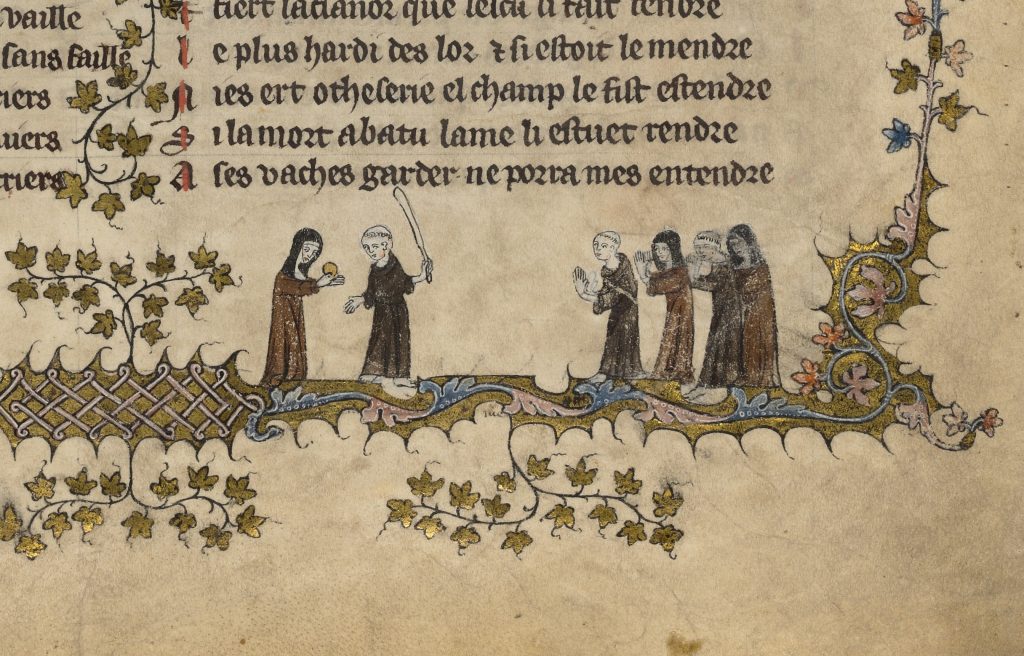

Yet there is evidence to suggest that baseball has far deeper historical roots, reaching back to the Middle Ages. The marginal decoration of a fourteenth-century French manuscript now in Oxford’s Bodleian Library (MS. 264) includes what may be the earliest conclusive illustrations of the game, played here by a group of nuns and monks. The nun at left has caught the ball just after the monk at bat has swung and missed. The monk turns to argue the count as two monks and two nuns in the infield raise their hands, ready to field, in a classic example of what Otto Pächt has called “simultaneous narrative.” The absence of outfielders in the scene was surely the result of artistic economy, given the limited space afforded by the gilded floral and foliate border, a decorative form that perhaps inspired the much later planting of ivy on the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, where players still contend with limited space.

The representation of the game’s players as cloistered religious figures offers a note of accuracy, as French nuns are in fact the earliest recorded players of the game that they called le base-bal. As early as the twelfth century, the nuns of the Abbey of Fontevraud in particular had established a reputation for their high on-base percentage and daring in run-downs; a certain Wilgefortis is lauded in conventual records for her lusty swing and reliability in the clutch. Barnstorming throughout the Loire valley, the Fontevraud nuns found the women of other convents eager to meet them between the lines, although the same could not be said of the monks and canons they challenged, most of whom refused to play, claiming the women “couldn’t throw.” The mixed-gender matchup depicted in the fourteenth-century Bodleian manuscript reflects a later era, when the dominance of the Fontevraud lineup had faded into distant memory and monks became more willing to test their skills against their slugging sorores.

Conventual baseball faded in Europe in the sixteenth century as reformers like Martin Luther turned popular opinion against the “devil’s game,” describing it as a gateway to luxury and vice and also complaining that the action was “too slow.” Today, it is only pictorial traces like that in Bodleian 264 that preserve the vibrant medieval traditions that gave us “America’s pastime.”