It’s easy to assume that medieval iconography was unchanging: that after a particular way of representing a saint or scene was invented, it became fixed in tradition. Not so! Medieval iconography and the stories that lay behind it moved constantly with the times, adapting over the centuries to the local beliefs and practices of their surrounding communities. Many of these post-medieval adaptations were frankly anachronistic, as is the topic of the present post, which also happens to be of central importance here at the Index: coffee.

Coffee was not a medieval beverage; the earliest evidence of its consumption in this form derives from fifteenth-century Yemen, from where it spread to other parts of the Islamic world, reaching Ottoman-ruled Constantinople in the sixteenth century and western Europe soon after. Where it was traded most actively, it inspired import companies, coffeehouses, and coffee-centered social practices, eventually even percolating (!) into medieval artistic and legendary traditions to which it had no original connections at all.

One example of this trend is Saint George’s “coffee boy,” a name sometimes given to the small figure holding a vessel who rides behind the saint on certain Byzantine and “post-Byzantine” icons (Fig.1). The type for some time puzzled scholars, who now conclude, on the basis of written sources, that such scenes depict Saint George miraculously rescuing a Christian captive.

However, the path to this conclusion was once obscured by alternative local interpretations. One legend that still circulates today in some villages in Cyprus explains that Saint George was drinking coffee when news reached him of the princess he was to rescue from a dragon. With no further ado he mounted his horse, and the coffee boy immediately followed him with his beverage, allowing the saint to finish it on the ride. While the legend seems unlikely (to say the least), our interest lies in how this conflation came into being. Why would the explanation of this image rest on coffee, a beverage unknown either to the third-century saint or to the medieval icon painters who portrayed him?

To answer this, we must return to the two original legends that inspired this iconography. In the former, the young boy was captured by the Bulgarians. He was so handsome that their ruler made him a steward and kept the boy in his residence. On the same evening Saint George rescued him, the ruler had asked him to bring water for hand-washing during the supper in the palace. In the second instance, the boy was taken into captivity by the Saracens and was made the personal cupbearer of the Emir of Crete; he was in the act of offering a glass of wine to the Emir when Saint George appeared and rescued him. The first representations of this iconography, in which the boy holds either a cup or a ewer, appeared in the twelfth century and then spread in the Eastern Mediterranean, where they promoted the role of Saint George as defender of Christians in areas threatened by foreign invasion. Not surprisingly, the type became even more widespread in Orthodox icons after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottoman Empire.

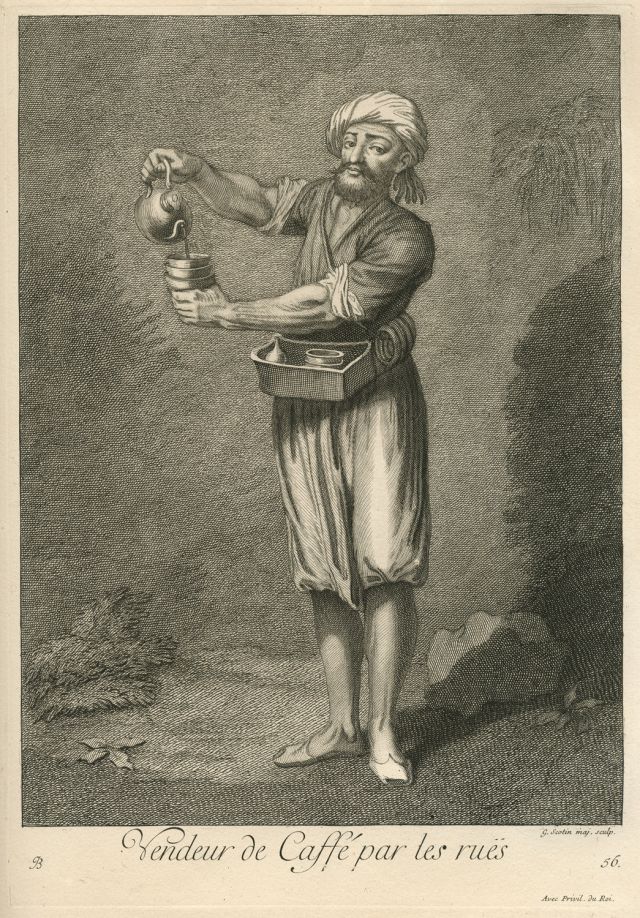

In this later period, the representation of the miracle of the captive boy was often conflated with the more famous episode of Saint George killing the dragon and saving the princess (Fig. 2). This compositional transition combines the two miraculous episodes to reinforce the original connotation of protection from “infidels,” embodied by the young boy, and of the fight against evil, symbolized by the dragon and the unharmed princess. After the sixteenth century, the garments worn by the young boy reflect contemporary fashion under the Ottoman rule: baggy trousers, a yelek (vest), a cebken (jacket) and a distinctive hat. The opacity of the ewer he holds, which resembled a coffee pot, may have led to the boy’s identification as a coffee server, much like the vendors found throughout Ottoman-ruled lands (Fig.3). Like so much medieval iconography, the interpretation of St. George’s “coffee” boy thus tells us much more about the preoccupations of a changing early modern society than it does about George’s own hagiography.

The association of coffee with St. Drogo, a French saint venerated at Sebourg, has even more circuitous history. Since about 1860, Drogo has been credited as the patron saint of coffeehouses, especially in Ghent, but the reasons for this remain obscure. A twelfth-century orphan, he early devoted himself to penance, pilgrimage, and charity, giving away all that he earned as a shepherd beside what he needed to stay alive (Fig. 4). When a painful hernia made work and travel impossible, he settled down as a hermit in Sebourg, living on a bare ration of brown bread and warm water until his death in 1186.

Drogo’s hagiography offers nothing that might link the saint to coffee besides his penchant for drinking warm water, and this might have encouraged his association with the beverage. However, it may be worth considering that in the mid-nineteenth century, when the saint’s link to coffeehouses is first recorded, his cult center of Sebourg was also renowned for the production of chicory, a plant used in combination with coffee and as a coffee substitute in both France and the Low Countries from the late eighteenth century onward. Could the local chicory trade have encouraged St. Drogo’s association with coffee drinking? We would love to hear from historians who may have an answer to this mystery.

Anachronisms aside, what St. Drogo and the “coffee boy” tell us quite clearly is how flexibly saints’ lives and iconography responded to the changing priorities of the communities around them. The same flexibility more recently has given us Saint Claire as the patron saint of television and Saint Isidore of Seville as patron of the internet. What new saintly protectors will the 21st century bring? There’s a question to ponder over your next cup of joe.

Contributed by Pamela Patton and M. Alessia Rossi.