Figure 1. Saint Nicholas of Myra Refusing Milk, ivory crozier, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1150-1185).

December 6 marks the feast day of Saint Nicholas of Myra, the source of our modern-day Santa Claus. We have taken this occasion to showcase the Index of Medieval Art as a tool for learning and researching about the iconography of medieval saints. The Index’s extensive collection of data had already offered users a chance to trace the saint’s history through art, and its archive of medieval images had granted researchers the opportunity to compare iconographies and expand their understanding of saints like Nicholas. Now, the multiple filters in the new database, currently in beta and undergoing daily refinements, allows users to retrieve, browse, and narrow search results in order to highlight the specificities of the saint.

The historical Saint Nicholas of Myra is an obscure figure. We know little more than that he was born in Asia Minor at the end of the third century and later in his life became a bishop of Myra. Nevertheless, he is one of the most popular saints of the Christian church, praised for his victories against demonic infanticide and his capacity of resuscitating dismembered bodies left in barrels to cure (yes, that’s right!). It should really come as no surprise, then, that the Index has 376 records of portraits and more than 600 representations of narratives and single figures of the saint.

But, if Nicholas’s life is virtually unknown, how did his cult and imagery develop to such a degree? The medievalists among our readers will already know that that the answer lies in another Saint Nicholas, that of Sion. The latter lived in the sixth century, and we have somewhat more information about him. Before the 10th century, these two saints, Nicholas of Myra and Nicholas of Sion, were merged by the literary tradition, and the voids left by the life of the former were filled by the latter. The fate of the two saints was sealed, and the archimandrite of Sion fell into darkness while the cult of the bishop of Myra flourished.

The cult of the bishop of Myra spread in both Eastern and Western Christendom. His life is represented in Byzantine monumental painting at least 31 times. The strengthening of his devotion saw a similar trend in the West. By the Renaissance, he had become the most popular saint in Europe. The Index allows for an interesting overview of the different contexts where Saint Nicholas’ cult developed. By browsing the Style/Culture filter, you can find 355 records identified as Gothic, 161 as Byzantine and 89 as Romanesque.

We know very little about Saint Nicholas’ childhood, but the Golden Legend assures us that he was incredibly pious from birth (literally):

While the infant (Saint Nicholas) was being bathed on the first day of his life, he stood straight up in the bath. And from then on, he took the breast only once on Wednesdays and Fridays.

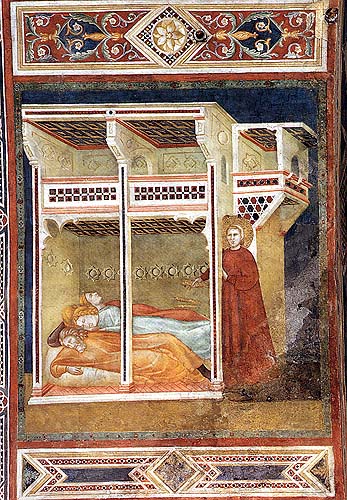

On a Crozier at the V&A, Saint Nicholas is represented sitting on his mother lap (Fig.1). She is offering her breast, but Saint Nicholas refuses, averting his head. With such a start, we should not be surprised that, as a young man, he decided to devote his inheritance to saving three sisters from prostitution (a real-life super hero!). The opportunity arose when a citizen of Myra lost all his money and could not support his three daughters. Nicholas heard of the situation and provided a dowry for each of the sisters. Among the 58 records with this subject identified in the Index database is a fresco in the chapel of Saint Nicholas in the lower church of San Francesco in Assisi (Fig.2). Here, he is represented as throwing three bars of gold through the window of a building where the three sisters and their father are sleeping.

Figure 2. Nicholas of Myra aiding the Dowerless Maidens, detail from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, San Francesco, Lower Church, Assisi (1300-1349).

The nature of the dowry in this tale ranges from bags to balls to bars to coins of gold. In western iconography, the three balls become an attribute of the saint, and scholars have suggested a link between this and the pawnbroker’s symbol of three golden spheres suspended from a bar.

Besides helping maidens, Saint Nicholas is also known as the guardian of sailors, an exorcist and healer. By using the Creator filter in the Index, it is possible to examine this dimension of Saint Nicholas’s through the eyes of many artists. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, for instance, painted on panel several scenes from the life of the Saint, including that of the Resurrection of the Strangled Boy (Fig.3). The scene takes place in a two-story house, with the narrative beginning on the upper floor with the banquet scene. During the feast, the devil came to the door, dressed as a pilgrim and asking for alms. The boy is represented first at the top of the stairs, answering the door, and later at the bottom while being strangled by the devil. The story continues to unfold in the foreground where the boy is resurrected by the rays descending from Saint Nicholas.

Figure 3. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting a Strangled Boy by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Panel painting in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (1300-1349).

Purely western is the peculiar story of Nicholas’s resurrection of three murdered boys. According to this tale, an innkeeper kidnapped and killed three youths. In the stained-glass window from Bourges Cathedral, they are shown reclining on a draped bed as the innkeeper raises his ax to kill them (Fig.4). At far right, Saint Nicholas extends his right hand in blessing toward the resuscitated boys, reflecting the legend’s account in which the innkeeper, having chopped up the boys, placed them in a barrel to cure. As an explanation for this, it is said that there was a famine during that year, and so the innkeeper was hoping to sell the cured meat as ham in order to make a living (sure, that makes total sense).

Figure 4. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting the three murdered boys, detail of a stained-glass window from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, Bourges Cathedral (1205-1220)

The range of stories and miracles performed by Saint Nicholas developed with the saint’s reputation as a healer and the protector of children, unmarried girls, merchants, sailors, pawnbrokers and scholars. His popularity overall is reflected in the Index. Using the Work of Art Type filter, you’ll discover that because of this widespread cult, Saint Nicholas can be found in 169 manuscripts, and on 22 painted panels, 4 book covers, 2 miters, and 1 ring. Similarly, by browsing the Medium filter, we learn that there are 140 instances of depictions of Saint Nicholas in fresco, 37 in embroidery, 17 in mosaic, 15 in ivory, 8 in enamel, and 2 in niello.

It is only fitting that we should end with the death of Saint Nicholas, from whose remains a fragrant oil was said to flow, an oil that performed many miracles. But the story doesn’t really end here. Saint Nicholas’ body was stolen in the 11th century by Italian merchants and brought to Bari where it has been kept ever since. However, recent archaeological excavations in the church of Saint Nicholas in Demre (once known as Myra) have brought to light an intact tomb (soon to be opened) beneath the floor. Some believe this to be the original tomb of Saint Nicholas. If there’s a body in this tomb, does that mean that the relics in Bari are not of the saint after all?

We hope that by exploring images of Saint Nicholas in our database, you’ll also discover the many ways in which the new Index of Medieval Art can help you with your research. The database offers users the opportunity to expand and challenge previously acquired knowledge using new (still developing) filters that aid in narrowing the search thematically, iconographically, and stylistically. We have plans for other features as the beta continues to develop (though, not always as fast as we would like) offering new tools for discovery. And although this ongoing, expansive repository called the Index of Medieval Art does not hold all the answers, we hope that it will prompt you to ask more questions.

Maria Alessia Rossi, Kress Postdoctoral Researcher