In northern climes, the beginning of February used to be reliably miserable. It was always the time of year when the sedentary heart of winter was covered in forgetful snow, and we took refuge indoors while the wasteland outside was feeding a little life with dried tubers (to paraphrase T.S. Eliot). Groundhog Day is in early February for a reason. Every year, in our collective longing for an early return of spring, we eagerly anticipate the meteorological insights of a skittish marmot. And so, despite the unseasonably warm temperatures in Princeton this week, we couldn’t help but explore some imagery traditionally associated with the month of February.

In many manuscript calendar illustrations, the occupational image for February depicts an interior scene, a room in which figures warm themselves before a fireplace. Seated at the hearth, a female servant, or perhaps the woman of the house, stokes the fire. Often in such scenes, a man sits at a table spread with food and dishes. The Index of Medieval Art subject heading identifies this scene as the “Labors of the Month, February.” Certain components of this subject, such as “Fireplace,” “Table,” and “Feasting,” also have their own subject designations.

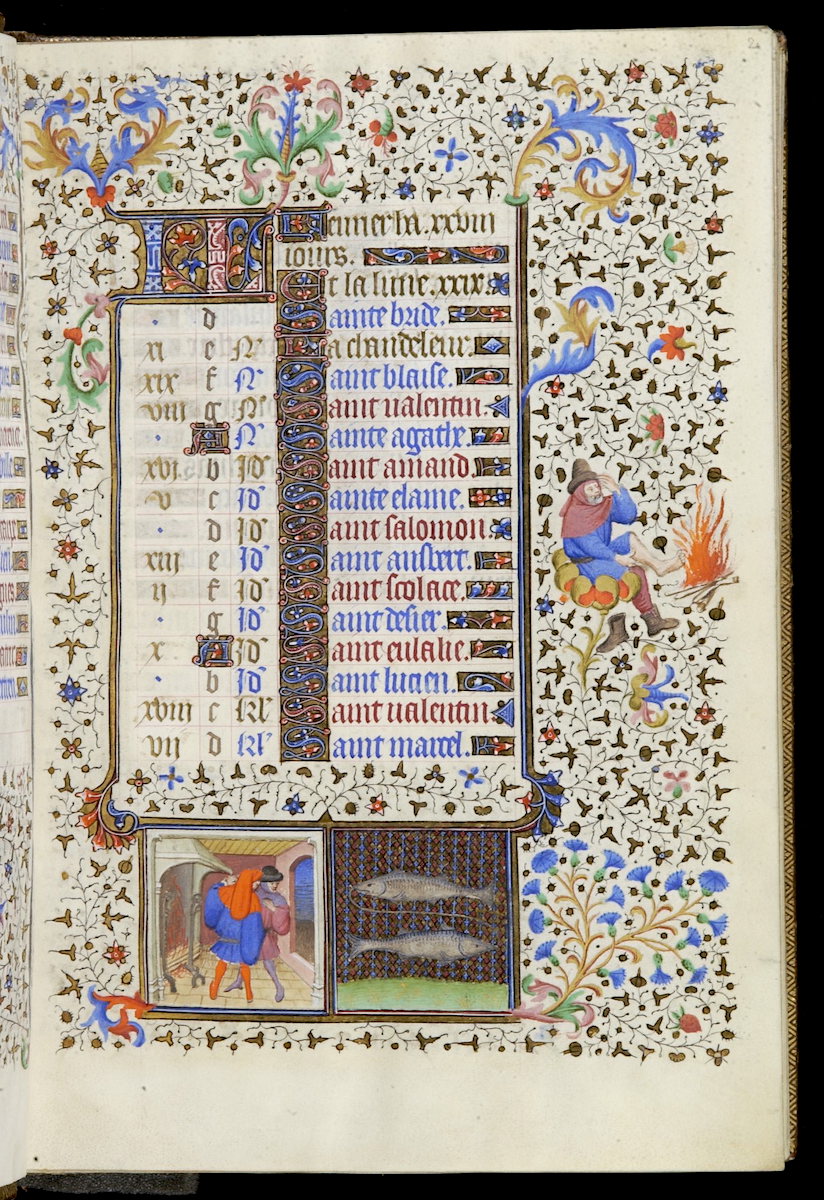

Other attributes common to the February warming scenes are figures performing such actions as blowing a bellows at the fire, cooking food in a pot over the flames, carrying bundled firewood indoors, or wearing heavy furs. A marginal miniature in the calendar of a fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Burgundy depicts a typical February scene with several of these domestic elements: a woman wearing a veiled headdress stokes a glowing fire in a simple stone fireplace while, behind her, a warmly dressed man seated at a draped table clings to a morsel of food (Fig. 1).

Searching the Index of Medieval Art database with simple keywords such as “fireplace,” and using the Subject Filter for “Labors of the Month, February,” will return a little more than seventy work of art records. Most of them appear in illuminated manuscripts. One such fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Paris or Flanders contains a February calendar page with two square miniatures of equal size in the lower margin. One of these paired miniatures shows the typical interior occupation of February, figures by the fire. The other shows the usual zodiac sign, Pisces, as a pair of fish lying head to tail with a line connecting them by their mouths. In the right margin, the artist created a comical moment: among the densely scrolled foliate borders, a man sitting on a fantastic flower raises his bare left foot toward some blazing logs (Fig. 2). In February, even marginalia need to warm their toes!

Other database filters will discover results illustrating February in different media, such as a man warming himself in the quatrefoil stone relief sculpture on the west façade of Amiens Cathedral. While this February figure sits and adjusts logs on the fire, his shoes are neatly placed in the foreground (Fig. 3). As is common for all twelve labors of the months, iconographic variants occur among these images, and monthly tasks are not fixed. Indoor cold weather occupations—including feasting, cooking, and baking—can be found in the previous months of January and December, often in similar compositions with fireplaces. February illustrations may also show outdoor scenes, such as slaughtering animals, fishing, digging fields, or pruning vines.

Keeping warm and dry during the winter months was a matter of survival for medieval people. Even today our good health and happiness are at risk in the winter. While its fires are long extinguished, this fine fifteenth- or sixteenth-century French limestone fireplace, today on display in the Met Cloisters, was likely once the architectural centerpiece of a home, and we can still imagine its appealing warmth (Fig. 4). Whether you are enjoying a restfully sedentary season or the official start of the spring semester has you thoroughly engaged in your own labors of the month, we wish you a warm and happy February!

The marketplaces of medieval Europe were redolent of the spices that purportedly first arrived with returning Crusaders. A taste for the flavors of cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger, pepper and the like created an increasing demand for spices that could not be grown in Europe’s climate but had to be imported from the East along secret trade routes, over land and sea. Distance was only one of several factors that affected the supply of spices, which were expensive and enjoyed only by those who could afford them. Nevertheless, as Paul Freedman writes in his blog “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced our World,” the new taste for exotic flavors helped encourage world exploration and turn spices into global commodities.

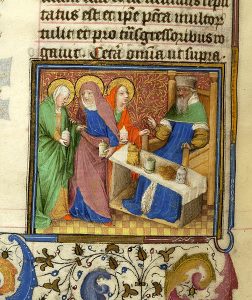

The uses of spices were both culinary and medical, and medieval cookbooks and herbals reveal that spices were part of preferred regimens. Spices were taken together in varying combinations, sometimes seasonal. In the cold and wet winter months, it was advisable to eat spices in strongly flavored food and drink to warm the body. Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat notes in her History of Food that the physician Arnau de Villanova (c. 1240-1311) recommended balancing the four humors of the body by consuming spices “proper for winter” as zesty sauces of ginger, clove, cinnamon, and pepper (Toussaint-Samat, 486). These spices would aid digestion after a heavy winter meal by heightening the effects of “hot” and “humid” properties in roasted meats. To this day, the warming spices advocated by Arnau de Villanova tend to be associated with fall and winter.

Cameline sauce, perhaps the original steak sauce, was the perfect accompaniment to roast meats. Prepared in summer and winter months alike, the sauce was so popular in some locations, such as fourteenth-century Paris, that the blend was usually readily available from the local sauce maker. There were regional varieties of Cameline sauce, too, and the “Tournais style” involved grinding together ginger, cinnamon, saffron and half a nutmeg. The spice powder was soaked in wine and stirred together with bread crumbs. The strained mixture was then boiled, with sugar added to make the winter variety of the sauce. One recipe for Cameline sauce has been adapted by Daniel Myers for the Medieval Cookery web site and is reproduced here with permission.

Cameline Sauce

3 slices white bread

3/4 cup red wine

1/4 cup red wine vinegar

1/4 tsp. cinnamon

1/4 tsp. ginger

1/8 tsp. cloves

1 tbsp. sugar

pinch saffron

1/4 tsp. saltCut bread in pieces and place in a bowl with wine and vinegar. Allow to soak, stirring occasionally, until bread turns to mush. Strain through a fine sieve into a saucepan, pressing well to get as much the liquid as possible out of the bread. Add spices and bring to a low boil, simmering until thick. Serve warm.

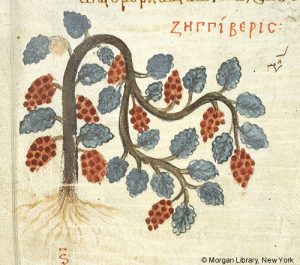

Ginger came to be highly prized during the Middle Ages, though the use of ginger can be traced back thousands of years in India and China. The potent ginger plant and rhizomes were valued for their stomach-warming and digestive properties as much as for the flavors they imparted. The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides advocated consuming a spicy Arabian plant called ζιγγίβερις (zingiberis), which was probably ginger, to “soften the intestines gently.” In Arabia, Dioscorides noted, they used only the freshest ginger plants (O’Connell 116-117).

Clove was known as one of the “lesser spices.” Though not as strong as ginger but useful for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, clove was especially useful in dental care.

Named in English and other languages—“clou de girofle” in French—for the resemblance of the bud to nails, clove originated in the Moluccan Islands of Indonesia, the historical core of the Spice Islands. As with ginger, clove had its earliest uses in India and China in the fourth-century BCE, finding its way to Roman and Greek markets by way of port cities on the Mediterranean. By the eighth century, clove was known throughout Europe and features in several historic dishes. It was also a typical spice in pomanders, the medieval precursor to potpourri, in which fragrant ingredients were placed in a perforated box to ward off illness. The decorative use of clove-studded oranges, a seasonal pomander, is still associated with the winter months.

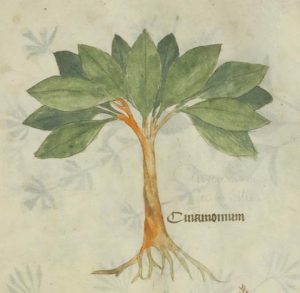

Hippocras, or hypocras, was a medieval spiced wine and popular cordial enjoyed especially during the winter holidays for several centuries. Hippocras was a concoction of powdered cinnamon, cassia buds, ginger, grains of paradise and nutmeg boiled with sugar and wine. Cinnamon, the essential flavor of hippocras, was a favorite spice of the medieval palate. Its mysterious origins generated many fanciful tales and even several expeditions. Perhaps most famously, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus thought he had located the spice in America—the Indies to him— and in 1493 he reportedly brought back bits of bark from a perfumed wild cinnamon tree that was not very tasty.

Long before Columbus, the ancient Egyptians had prized cinnamon as the “… goodly fragrant woods of The Divine Land…” while medieval Arabs believed that large birds used cinnamon sticks in their nests (O’Connell, 76-77). In the first century, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder rightly located the origin of cinnamon on the shores of the Indian Ocean. With information from some seasoned merchant, perhaps, Pliny knew that the cinnamon trade was dangerous and that a return trip to the source of the spice took almost five years. Pliny’s claims about the origin of cinnamon were eventually verified in the 1340s when the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1368) arrived at the island of Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) and discovered untouched miles of the cinnamon tree. Before its widespread appreciation as a culinary ingredient, cinnamon was prized in several ancient cultures as incense holding ritualistic importance, sometimes burned for its fragrance on a funeral pyre.

The final “proper” winter spice is pepper. With a name widely applied to many spices, including the black and white varieties, pepper was perhaps the most familiar spice of the Middle Ages. Both black pepper and white pepper are obtained from the small berries of the Piper nigrum vine.

Unripe berries are green, and ripe berries are red. Dried ripe berries yield white pepper, and despite the fantastic medieval legend propagated by Isidore of Seville (560–636) that the scorching of pepper crops blackened the berries and drove out the poisonous guard snakes, unripe pepper berries are simply plucked, gathered, cooked, and then dried to give us the most familiar variety, black pepper. The principal traders of pepper came from India where the vines thrived in tropical regions. Pepper was used in medicine to aid digestion and to treat ailments like gout and arthritis, as well as infectious diseases like the bubonic plague.

The term “peppercorn rent” derives from the practice established in early common law in England that payment of rent or tax might be made by a peppercorn, to avoid the bother of exchanging real currency. Usually no peppercorns were actually collected during these transactions, but the spice represented a hard asset, and the term is still in use today in legal parlance to describe a token amount of rent money paid in order to keep a title alive. In all seasons, spices and their increasingly globalized trade during the Middle Ages affected medieval economies, and brought social, culinary, and health benefits to Europe. To this day, the flavors and aromas of medieval markets spice up the long, cold winter months.

Sources

Paul Freedman, “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced Our World,” The YaleGlobal Online Blog, March 11, 2003, http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/spices-how-search-flavors-influenced-our-world.

Daniel Myers. “Cameline Sauce.” Medieval Cookery. Last modified July 13, 2006. http://medievalcookery.com/recipes/cameline.html.

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and Medieval Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Translated by Anthea Bell. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Leah Hyslop, “Where do Christmas spices come from?” The Telegraph.co.uk (blog), December 22, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/grow-to-eat/where-do-christmas-spices-come-from/

O’Connell, John. The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary. London: Profile Books, 2015.